|

Animal Welfare and Organic Certification Norms

Short description:

Species specific welfare issues for cattle, goats, chicken, pigs and sheep

|

Animal Welfare

Introduction

Livestock husbandry is based on the harmonious relationship between land, plants and livestock, respect for the physiological and behavioral needs of livestock and the feeding of good-quality feed stuffs.

Animals should also be fed in a way they would in the wild. For example foraging animals such as guinea pigs should have their food scattered and different fresh fruit and vegetables should be hidden in hay to make them work for it. This stimulates their mind and body, prevents boredom and reduces stress. If they don't have the chance to do this they may exhibit abnormal, stereotypical behaviors.

Animals should be free from discomfort, pain, injury and disease. If animals are in an unsuitable environment where it's too hot, too cold or wet, then they will become stressed and will become ill. If they're in pain or are suffering from a disease that isn't treated then they will exhibit abnormal behaviors such as avoiding food, apathy and aggression. All of these factors contribute to the psychological welfare of animals.

Animals, for their physical and psychological well being need to be able to exhibit their natural behaviors that they would perform in the wild. For example

- Chicken need to be able to have dust baths and make nests for their eggs, if they don't then they will cause harm to themselves.

- Battery farmed egg laying chickens will rub themselves against the dirty cage bars causing injuries to their eyes, beaks and feathers.

- Battery farmed pigs in crates will bite the bars causing injuries to their mouths if they're not allowed to forage. Being able to perform natural behaviors makes them happy.

With performing natural behaviors animals need to be kept with their own kind, for example

- Sheep feel safe in a large group, and if kept solitary will become bored and stressed, they become agitated, apathetic and perform stereotypical behaviors if they're in this situation.

- Being able to breed is also a form of natural behaviors; the vast majority of bucks will not mount in an unstable slated floor as they're afraid of sliding and breaking their legs.

- Animals need to be free from fear and distress, for example chicken housed near a barking dog will become stressed and cause abnormal behaviors such as not eating or sleeping. Animals need to be able to hide to make them feel secure and this will make them more secure and confident.

The physiological needs of livestock vary with class, age, and breed of animal. For instance, lactating cows and first calf heifers have high demands in terms of digestible energy and crude protein. To maximize gains, yearlings and steers require good quality forage. Dry cows do not need as high a level of nutrition.

Larger breeds have higher forage requirements based entirely on body size. This becomes a more important factor during lactation. Breeds producing more milk and larger calves have higher energy requirements and may require supplementation or better quality forage if they are to maintain milk production and be ready for re-breeding. Different breeds and species of grazing animals exhibit distinct preferences for both forages and terrain. Where possible, managers should select the kind of grazing program which makes best use of the forage resource.

Behavior influences animal concentration

Concentration areas are potential water quality concerns due to increased levels of livestock waste and due to the trampling of vegetative cover needed to reduce pollutant transport. The location of concentration areas in relation to streams generally determines their water quality significance. A preferred watering point, as described previously, is a typical example of a concentration area that may impact water quality.

In addition to being a common type of concentration area, preferred watering location is also the major factor influencing the location of other types of concentration areas. Other factors that determine concentration area locations include shade, prevailing wind direction, mineral supplement, and fly control facilities in the hot season, and the availability of feed and protection from cold winds in the cold season.

Shade preferences are clearly influenced by proximity to preferred water and by prevailing wind direction. Other factors believed to influence shade preference are:

- The presence of biting insects,

- The likelihood of wind blowing under the tree canopy, and

- The quality of the shade.

Behavior influences grazing distribution

Grazing distribution can significantly affect water quality. Runoff will begin sooner and flow faster over heavily grazed areas relative to more moderately-grazed areas. If adequate vegetative cover does not separate these areas from waterways, runoff will increase pollutants deposited into streams. In these cases, modification of grazing behavior is needed to benefit water quality.

Improving grazing distribution requires management of animal movement and selective grazing behavior to create a mosaic of vegetative cover that is generally uniform over the pasture. To protect water quality, heavy grazing use in draws or near streams should be minimized by enticing livestock to spend a greater amount of time elsewhere.

Many of the same behavioral factors that help determine the location of concentration areas also influence grazing distribution. Watering location and prevailing wind direction are, again, most prominent. The presence of obstructions such as abandoned fences also influences grazing patterns. Removing abandoned fences may be needed to allow unrestricted livestock movement in order to achieve a more uniform grazing distribution.

Foraging behavior will also have an effect on grazing patterns. Cattle will spend a disproportionate amount of their time in accessible areas with quality forage. This is because foraging efficiency plays an important role in determining grazing patterns. This role involves a balance between nutrient intake and energy expenditure by the animal.

Topography and distance to water are factors affecting energy expenditure by livestock to acquire nutrients.

Organic Certification Norms

General principles for Organic management and certification:

Organic agriculture is based on:

1. The principle of health

2. The principle of ecology

3. The principle of fairness

4. The principle of care

2. The principle of ecology

3. The principle of fairness

4. The principle of care

The principles are to be used as a whole. They are composed as ethical principles to inspire action.

Principle of health

Organic Agriculture should sustain and enhance the health of soil, plant, animal, human and planet as one and indivisible.

This principle points out that the health of individuals and communities cannot be separated from the health of ecosystems - healthy soils produce healthy crops that foster the health of animals and people. Health is the wholeness and integrity of living systems. It is not simply the absence of illness, but the maintenance of physical, mental, social and ecological well-being. Immunity, resilience and regeneration are key characteristics of health.

The role of organic agriculture, whether in farming, processing, distribution, or consumption, is to sustain and enhance the health of ecosystems and organisms from the smallest in the soil to human beings. In particular, organic agriculture is intended to produce high quality, nutritious food that contributes to preventive health care and well-being. In view of this it should avoid the use of fertilizers, pesticides, animal drugs and food additives that may have adverse health effects.

Principle of ecology

Organic Agriculture should be based on living ecological systems and cycles, work with them, emulate them and help sustain them.

This principle roots organic agriculture within living ecological systems. It states that production is to be based on ecological processes, and recycling. Nourishment and well-being are achieved through the ecology of the specific production environment. For example, in the case of crops this is the living soil; for animals it is the farm ecosystem; for fish and marine organisms, the aquatic environment.

Organic farming, pastoral and wild harvest systems should fit the cycles and ecological balances in nature. These cycles are universal but their operation is site-specific. Organic management must be adapted to local conditions, ecology, culture and scale. Inputs should be reduced by reuse, recycling and efficient management of materials and energy in order to maintain and improve environmental quality and conserve resources.

Organic agriculture should attain ecological balance through the design of farming systems, establishment of habitats and maintenance of genetic and agricultural diversity. Those who produce, process, trade, or consume organic products should protect and benefit the common environment including landscapes, climate, habitats, biodiversity, air and water.

Principle of fairness

Organic Agriculture should build on relationships that ensure fairness with regard to the common environment and life opportunities.

Fairness is characterized by equity, respect, justice and stewardship of the shared world, both among people and in their relations to other living beings.

This principle emphasizes that those involved in organic agriculture should conduct human relationships in a manner that ensures fairness at all levels and to all parties - farmers, workers, processors, distributors, traders and consumers. Organic agriculture should provide everyone involved with a good quality of life, and contribute to food sovereignty and reduction of poverty. It aims to produce a sufficient supply of good quality food and other products.

This principle insists that animals should be provided with the conditions and opportunities of life that accord with their physiology, natural behavior and well-being. Natural and environmental resources that are used for production and consumption should be managed in a way that is socially and ecologically just and should be held in trust for future generations. Fairness requires systems of production, distribution and trade that are open and equitable and account for real environmental and social costs.

Principle of care

Organic Agriculture should be managed in a precautionary and responsible manner to protect the health and well-being of current and future generations and the environment.

Organic agriculture is a living and dynamic system that responds to internal and external demands and conditions. Practitioners of organic agriculture can enhance efficiency and increase productivity, but this should not be at the risk of jeopardizing health and well-being. Consequently, new technologies need to be assessed and existing methods reviewed. Given the incomplete understanding of ecosystems and agriculture, care must be taken.

This principle states that precaution and responsibility are the key concerns in management, development and technology choices in organic agriculture. Science is necessary to ensure that organic agriculture is healthy, safe and ecologically sound. However, scientific knowledge alone is not sufficient. Practical experience, accumulated wisdom and traditional and indigenous knowledge offer valid solutions, tested by time. Organic agriculture should prevent significant risks by adopting appropriate technologies and rejecting unpredictable ones, such as genetic engineering. Decisions should reflect the values and needs of all who might be affected, through transparent and participatory processes.

Animal Management: General principles, Nutrition, Mutilation, Medicine, Transport

For all species, the following general principles apply in organic certification:

- Landless animal husbandry systems are prohibited.

- The operator shall ensure that the environment, the facilities, stocking density and flock/herd size provides for the behavioral needs of the animals.

- In particular, the operator shall ensure that the livestock as:

a) Sufficient free movement and opportunity to express normal pattern of behavior, such as space to stand naturally, lie down easily, turn around, groom themselves and assume all natural postures and movements.

b) Sufficient fresh air, water and feed to satisfy the needs of the animals;

c) Access to resting areas, shelter and protection from sunlight, temperature, rain, mud and wind adequate to reduce animal stress - Animals should not be kept in isolation from other animals. Farmers may isolate bulls, sick animals and those about to calve.

- Construction materials and production equipment that might significantly harm human or animal health shall not be used.

- Farmers shall manage pests in livestock housing and shall use the following methods according to these priorities:

a) Preventative methods such as disruption, elimination of habitat and access of facilities;

b) Mechanical, physical and biological methods.

c) Substances according to the appendices of this standard.

d) Substances (other than pesticides) used in traps. - when animals are housed, the farmer shall ensure that:

a) where animals require bedding, adequate materials are provided;

b) building construction provides for insulation, heating, cooling and ventilation of the building, ensuring that air circulation, dust levels, temperature, relative air humidity, and gas concentrations are within levels that are not harmful to the livestock;

c) no animals shall be kept in cages;

d) Animals are protected from predation by wild and feral animals. - Where livestock are housed, the minimum "on-ground" density for the indoor area shall be not more than the following:

| Type of animal | Maximum density |

| Bovine and Equine(adults) | 4.0m2/animal |

| Sheep and goats (adults) | 1.5m2/animal |

| Porcine (>40kg) Sow with piglets |

1.0m2/animal 3.0m2/animal |

| Poultry(adults) | 6.0m2/animal |

| Rabbits | 0.3m2/animal |

- All animals shall have unrestricted and daily access to pasture or a soil-based open-air exercise area or run, with vegetation, whenever the physiological condition of the animal, the weather and the state of the group permit. Such areas may be partially covered. Animals may temporarily be kept indoors because of inclement weather, health condition, reproduction, specific handling requirements or at night. Lactation shall not be required a valid condition for keeping animals in-door.

- The maximum hours of artificial light used to prolong natural day length shall not exceed a maximum that respects the natural behavior, geographical conditions and general health of the animals. For laying hens, a minimum daily rest period of 8 continuous hours without artificial light shall be respected.

Animal Nutrition

General principle

Animals receive their nutritional needs from feed of good quality and as much as possible from organic sources.

Requirements:

Animals shall be offered a balanced diet that provides all the nutritional needs of the animals in a form allowing them to exhibit their natural feeding and digestive behavior.

Prohibited substances (not allowed under organic certification norms) in the diet:

a) Farm animal by-products (e.g. abattoir waste) to ruminants;

b) Slaughter products of the same species;

c) All types of excrements including droppings dung or other manure;

d) Feed subjected to solvent extraction (e.g. hexane) or the addition of other chemical agents;

e) Amino-acid isolates;

f) Urea and other synthetic nitrogen compounds;

g) Synthetic growth promoters or stimulants;

h) Synthetic appetizers;

i) Preservatives, except when used as a processing aid;

j) Artificial coloring agents.

b) Slaughter products of the same species;

c) All types of excrements including droppings dung or other manure;

d) Feed subjected to solvent extraction (e.g. hexane) or the addition of other chemical agents;

e) Amino-acid isolates;

f) Urea and other synthetic nitrogen compounds;

g) Synthetic growth promoters or stimulants;

h) Synthetic appetizers;

i) Preservatives, except when used as a processing aid;

j) Artificial coloring agents.

Allowed additives to feed:

- Animals may be fed vitamins, trace elements and supplements from natural sources.

- All ruminants shall have daily access to roughage. Ruminant must be grazed throughout the entire grazing season(s).

- Fodder preservatives such as the following may be used:

a) Bacteria, fungi and enzymes;

b) By-products of food industry (e.g. molasses);

c) Plant based products. - Young stock from mammals shall be provided maternal milk or other milk from their own species and shall be weaned only after a minimum period as specified below:

a) Calves and foals: 3months

b) Pigs:6 weeks

c) Lambs and kids: 7 weeks

Mutilations

General principle

Organic farming respects the animal's distinctive characteristics.

Requirements:

Mutilations are prohibited.

| Regional or other exception at certification body discretion

The following exceptions may be used only if animal suffering is minimized and aesthetics are used where appropriate:

a) Castrations;

b) Tail docking for lambs; c) Dehorning; d) Ringing; e) Mulesing only for breeds that require mulesing. |

Veterinary Medicine

General principle

Proper management practices promote and maintain the health and well-being of animals through balanced nutrition, stress-free living conditions and breed selection for resistance to diseases, parasites and infections.

Requirements:

- The farmer shall take all practical measures to ensure the health and well being of the animals through preventative animal husbandry practices such as:

a) Selection of appropriate breeds or strains of animal;

b) Adoption of animal husbandry practices appropriate to the requirements of each species, such as regular exercise and access to pasture and/or open air runs, to encourage the natural immunological defense of the animal to stimulate natural immunity and tolerance to diseases;

c) Provision of good quality feed;

d) Appropriate stocking densities;

e) Grazing rotation and management. - If an animal becomes sick or injured despite preventative measures, that animal shall be treated promptly and adequately, if necessary in isolation and in suitable housing. Farmers shall use in priority natural medicines and treatments, including homeopathy, Ayurvedic medicine and acupuncture whenever appropriate. Where this is not available, ask your vet for least environmentally damaging solutions.

- Substances of synthetic origin used to stimulate production or suppress natural growth are prohibited (not allowed in organic certification schemes.

- Vaccinations are allowed only if the following are the cases (Please consult your vet):

a) When an endemic disease is known or is expected to be a problem in the region of the farm and where the disease cannot be controlled by other management techniques, or

b) When a vaccination is legally required.

Transport and slaughter

General principle

Animals are subjected to minimal stress during transport and slaughter.

Requirements:

- Animals shall be handled calmly and gently during transport and slaughter.

- The use of electric prods and other such instruments is prohibited.

- Animals shall be provided with conditions during transportation and slaughter that reduce and minimize the adverse effects of: stress, loading and off-loading, mixing different groups of animals, extreme temperatures and relative humidity. The type of transport shall meet the specific needs of the species being transported.

- The farmer shall ensure an adequate food and water supply during transport and at the slaughter house.

- Animals shall not be treated with synthetic tranquilizers or stimulants prior to or during transport.

- Each animal or group of animas shall be identifiable at each step in the transport and slaughter processes.

- Slaughter house journey times shall not exceed eight hours.

- Those responsible for transportation and slaughtering shall avoid contact (sight, sound or smell) of each live animal with dead animals or animals in the killing process.

- Each animal shall be stunned before being bled to death. The equipment used in stunning shall be in good working order.

Species specific welfare issues for cattle, goats, chicken, pigs and sheep

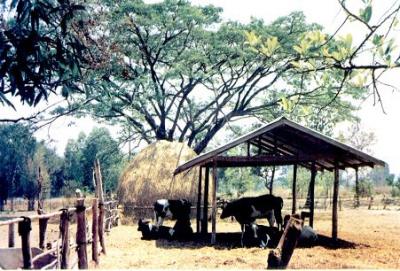

Cattle

1. Hunger and thirst

Cows spend 7-9 hours a day grazing and nearly the same amount of time ruminating the ingested feed. Adequate provision of fibre is an essential requirement for a healthy rumen environment. Fibre ranging from 7-10 cm in length (approximately the width of the muzzle) is optimum and prevents cattle selecting through the ration and discarding longer fibre. Long fibre stimulates cudding, which in turn stimulates saliva production, and saliva is the primary rumen buffer, preventing acidosis. The optimum forage to concentrate ratio to maintain rumen health and pH at 6 - 6.8 is 60:40 on a dry matter basis (roughage: concentrate). Rumen acidosis is the most common forage related stress that we see in dairy cattle. Rumen acidosis is primarily due to inadequate levels of effective fibre in the rations of those cows. High yielding cows are commonly fed diets containing 45 - 55 % forage on a DM basis. Finishing beef cattle are often fed a diet consisting of 25 - 40% forage on a DM basis.

2. Freedom from discomfort

A long lying period is important in the prevention of lameness in dairy cows, and it has also been noted that cows spend significantly more time lying down ruminating, as opposed to standing ruminating. Because a large percentage of cattle time is spent ruminating whilst loafing, dry comfortable hygienic bedding that encourages cows to lie down is highly important.

3. Freedom from pain, injury or disease

Hygienic bedding material in order to minimize the risk of mastitis is a priority. Being able to lie down is very important to cattle. When given choice and optimum conditions, cows are known to spend 50% or more of their time lying down. A comfortable resting surface is an important aspect in encouraging cows to lie down. Cattle prefer dry, soft, insulating bedding, and subsequently show reduced incidence and severity of leg injuries.

In addition, the following need to be adhered to:

In addition, the following need to be adhered to:

- Stocking Rate: A stocking rate of 1 to 1.4 Lu's/ha is suitable for organic farming.

- Soil Fertility: It is easier to farm organically where soil fertility is medium to high. Rock phosphate has been used successfully on organic farms.

- Livestock System: Suckler cows and sheep are suited to organic farming. Under good husbandry natural immunity to parasites and diseases can develop. A grazing system which reduces the worm burden should be established.

- Clover: Clover is essential at higher stocking rates. Good clover stands can double pasture production, grass quality and animal performance is improved.

- Tillage: Some tillage is a major bonus. It provides cheaper grain and straw and allows the renewal of grassland. From 2008 only organic cereals can be fed to ruminants.

- Housing: The conventional straw bedded sheep house conforms to organic standards. In cattle housing a straw bedded lying area is essential (the feeding area may be slatted).

|

|

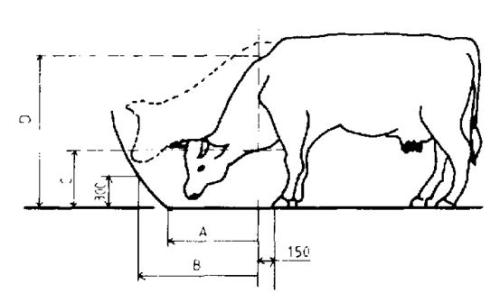

Minimum space allowances in loose cattle housing are as follows:

| Breeding and fattening cattle. (Live weight kg) | Lying area (metres squared per head) | Additional area (metres squared per head) | Total available area (metres squared per head) |

| Up to 100 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 2.6 |

| Up to 200 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 4.4 |

| Up to 350 | 1m2 per 100kg (with a minimum of 5m2) | 0.75m2 per 100kg (with a minimum of 3.7m2) | 1.75m2 per 100kg (with a minimum of 8.7m2) |

| Dairy cows | 6 | 4.5 | 10.5 |

The lying area must be under cover and bedded. The additional area may be inside or outside and does not have to be bedded.

Cubicle design

Cubicle management should be similarly careful, and the number of cubicles should always exceed the number of cows in each housing area and group by a minimum of 5%. Cubicles should be of adequate size (no specific "organic" cubicle standards are given) and of appropriate design and in good repair

Cubicle dimensions

- length 2.4m (solid front), 2.2m (head to head, open-fronted);

- width 1.1-1.2m with flexible (rope) bottom rail in divisions;

|

|

Cubicle design

- minimum height for solid divisions and head-end dividers should be 1.14m, so that a cow has enough room for head movement when standing up and lying down;

- flexible bottom rail in cubicle divisions;

- 12.7cm drop (slope) from front of cubicle to the back;

- maximum 12.7cm kerb;

- concrete fillet or a pyramid at the front of the cubicle to position the lying cow far enough back in the cubicle;

Cubicle surface

- concrete surface should always be covered with some type of bedding;

- constructing threshold or "lips" to maintain bedding in the cubicle must be avoided to avoid retention of urine and faeces;

- lime can be used in cubicles, but should be applied under fresh bedding, not on top of it;

- If the slurry passages are too narrow and dirty, even good cubicles fail to keep cows clean and to prevent lameness. Wider than standard 2.5 meter slurry passages should be considered, as this would improve health and decrease social stress in the herd.

An alternative guideline for dimensions is shown below:

| Cubicle length | Cubicle clear width | |

| Cow weight (kg) | including kerb (m) | between partitions (m) |

| 300 - 500 | 2.00 | 1.00 - 1.10 |

| 500 - 600 | 2.15 | 1.10 - 1.15 |

| 600 - 700 | 2.3 | 1.15 - 1.20 |

| 700 - 800 | 2.50 | 1.20 - 1.30 |

All housing for cattle should include an adequate provision of calving pens and sick pens for isolation of sick or injured animals. All cattle farms should also have provision for isolation and quarantine of bought-in animals in a separate building, unless the herd is genuinely closed and never buys in replacement or breeding animals.

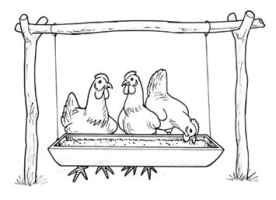

Feeding trough: should allow enough room for nozzle of the animal without apparent injury.

|

| Body scoring |

| © fao.org |

- Lameness - One should score lameness on a yes/no basis as cows walk out of the milking parlor. Score yes if the animal walks with an obvious limp and is still able to keep up with the herd. Five percent obvious limp is excellent. Over 10% of lactating cows with an obvious limp not acceptable. Lameness is caused by a combination of poor management and failure to select breeding stock with good feet and legs. Score 50 to 100 cows.

- Body Condition Score - Ninety percent of the lactating cows must have a body condition score of more than 2 and less than 3% with a score of less than 2. A score of 2 is the minimum acceptable body condition score

- Care of Newborn Calves - Calves must be fed colostrum within a few hours of birth. Calves must be dry and able to walk easily and stand without assistance from a person before they are transported off the premises. The only exception to this guideline is transport of calves to a local calf raising facility that is less than 2 hours away by road. Calves must be kept clean. There is a problem that needs to be corrected if over 5% of the calves are dirty.

- Clean Water provision at all times - This is required for both welfare and food safety reasons.

- Dehorning - Calves should be dehorned before 4 months of age. Older calves will require an anesthetic for dehorning.

- The routine practice of tail docking should be discouraged.

Goats:

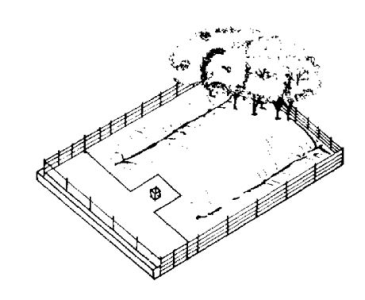

A few exceptions to the Standard allow temporary total confinement at times. These include inclement weather, health and safety issues and risk to soil or water quality. Nevertheless, to be certified organic, dairy goats cannot be totally confined for all or even a majority of their lives.

The Organic Standards also address pasture fencing. They prohibit the use of treated wood, where it may come into contact with soil crops or the goats. While older fencing may be grandfathered in, farmers who are starting with a new farm or replacing old fencing need to be aware of this prohibition and avoid using treated wood in fence construction.

Pasture

In order to be certified organic, goats must be raised on pasture that is certified organic. This requires that no pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilizers or any other restricted materials be used. Unless the pasture land to be used for goats is already certified, obtaining initial certification will take time.

In order to get initial certification for pasture land, a farmer must be able to show that no prohibited substance has been applied for 36 months prior to full certification. Dairy goat farmers who recently purchased property may have a harder time getting certified unless the prior owner is willing to assist with proving that no prohibited substances were applied. This is something to keep in mind when purchasing new property with plans to raise organic dairy goats.

Another important aspect of raising organic dairy goats is the need to avoid overstocking - which will lead to overgrazed pasture land. Overgrazed pasture, or pasture otherwise lacking vegetation, is not considered pasture under the certification standards anymore than a feedlot.

To ensure that the requirement for no spraying is met, if a pasture abuts a roadway where a county or other municipality may spray the roadside for weeds, put up signs indicating that the property is an organic farm and spraying is prohibited. Contact the municipality as well, to ensure that you meet their needs for any other required documentation.

In organic management of goats, pasture rotation is extremely important because using most chemical dewormers is prohibited. Pasture rotation discourages parasite overpopulation, especially in warm, wet regions, as well as discouraging overgrazing and allowing time for vegetation to rest and regrow.

Feed and supplements

Organic livestock may be fed only hay, grain, milk replacer, minerals and any other supplement that is certified organic. This means that it may not be genetically modified and may not contain synthetic hormones, antibiotics, coccidiostats or other restricted materials. Goats may not be given any of those additives directly, either. The bedding used for goats must also be certified organic, whether it is straw or saw dust because goats may eat the bedding.

An exception to the 100% organic requirement is for a dairy goat herd that is being converted to organic management. The products from these goats may be marketed as transitional while the farmer is working toward organic certification. The goats may be fed up to 20% conventional feeds for the first nine months of the transition, but then they must receive 100% organic feeds.

One major change that some dairy goat farmers who are switching to organic production will have to face is how they manage the kids. Kids may be bottle-fed with milk replacer only on an emergency basis. This is because dam-raising is more natural and sustainable, and no organic milk replacer currently exists for goat kids.

Another potential impediment is meeting the feeding requirements for their dairy goats. The area of the country, as well as the amount of land a goat farmer has available may make 100% organic feed impossible. Small holder farmers and in the semi-arid region, for instance, will be unable to grow their own hay, alfalfa and grain and will need to rely on what is available commercially. In some areas, finding organic feeds is next to impossible. In many cases, despite availability, the cost is prohibitive. Each farmer needs to determine what these costs will be, along with the market rate for organic milk or other dairy products, to determine whether raising organic goats is economically feasible. Those with small dairy goat herds who want to go organic for purely personal reasons may find it worthwhile to search out organic feeds, despite the high prices.

Health care

Health care can be one of the most challenging aspects of raising dairy goats organically. A goat cannot be certified organic if it has been treated with antibiotics, or a synthetic or non-synthetic substance that is prohibited by the law. Yet, goats do get sick with diseases that require the use of such substances. In fact, producers must treat sick animals, even if doing so will cause them to lose their status as "organic". So the challenge is, whenever possible, to find treatment methods that are organic and that work.

The Livestock Healthcare Standard requires producers to use preventive health care practices (vaccination is allowed), not treat goats that are not sick (e.g., giving antibiotics or dewormers routinely), and make sure the goats' living conditions and feed ration promote good health.

One of the most difficult health care problems encountered when raising goats organically is controlling parasites.

The Organic Health Standard also requires that physical alterations - such as tattooing or other identification, disbudding and castration - be done only in a way that promotes the welfare of the goat and minimizes pain and stress. Although there are no hard and fast rules, these are areas that must be addressed in an Organic System Plan and farmers need to be able to show that the way they perform these procedures meets the criteria.

Organic goat farmers need to educate themselves and make sure that their veterinarian is aware of organic standards in regard to medications that are often recommended or prescribed for goats. Consider giving them a copy of the regulations or the Livestock Workbook if they are not already familiar with the program. That way you can work together to determine how best to treat your goats when they do get sick and not mistakenly give a prohibited drug.

Other considerations

Recordkeeping is critical to raising goats organically and dairy goat farmers need to set up a recordkeeping system prior to applying for organic certification. Required records include "all records of the operation," and they must be understandable and available for inspection. Some of these records include identification for each goat including whether it was born on the farm or purchased, all veterinary and other health records for each goat, and feed information, which includes keeping all feed tags from feed that is purchased. These records can also serve a secondary purpose of tracking health issues to determine whether a certain goat or a certain line should be culled.

The standard also addresses requirement for processing of goat products. For example, organic meat may not come in contact with non-organic meat and no synthetic materials may be used during its processing. Farmers need to review the standard to determine whether other requirements for food processing will affect their operation and whether they can be met.

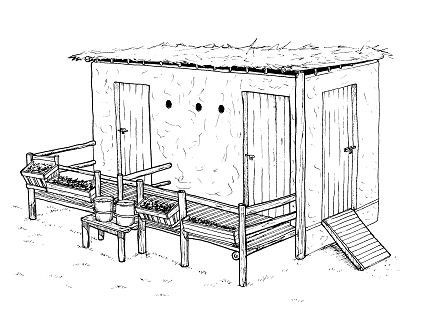

Housing

|

|

A good goat house should be

- Rain proof

- Damp proof

- Well ventilated

- Free from direct wind

- Free from sharp objects that might cut the goat

- Pest and wild animal proof

- Slats on floor for free fall of droppings

- With an area of at least 2meters per animal

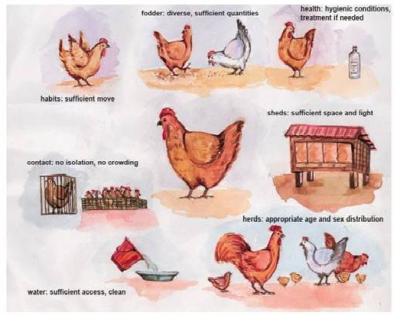

Chicken

The general requirements for organic chicken raising include:

- Poultry or poultry products must come from chickens that have been under organic management from the second day of life. If one cannot verify this they are not raising organic chickens.

- All feed, except minerals and vitamins, must be organically produced. Non-synthetic vitamins are preferred, but synthetic sources are allowed if non-synthetics are not available. The following are prohibited:

i. Animal byproducts from mammals and poultry, such as meat and bone meal, may not be included in rations.

ii. Fishmeal is not permitted, because of the difficulty of determining if they were organically produced.

iii. Synthetic amino acids are not permitted.

iv. Non synthetic but non agricultural products are permitted. - The handling of feed ingredients must comply with organic requirements. Some people may buy organic feed from mills or grow their own ingredients for feed, but organic guidelines must be followed with either choice.

- No drugs may be used to promote growth.

- Physical alterations such as beak trimming and toe trimming are permitted to promote the welfare of the animal or flock. These are still discouraged and would be handled on a case by case basis.

- Living conditions must be established and maintained to "accommodate the health and natural behavior of animals, including access the outdoors, shade, shelter, exercise areas, fresh air, and direct sunlight."Continuous confinement in cages is not permitted, but temporary confinement is allowed if adequately justified.

- Dust wallows are required, as is clean, dry bedding. Any bedding that is of a type typically consumed by poultry must meet all organic standards.

- Birds are not permitted to come into contact with treated wood used to construct chicken pens.

- Health care measures must include preventive practices such as good nutrition, sanitation, healthy living conditions and vaccinations. Antibiotics are not permitted. Synthetic parasiticides including coccidiostats are not permitted. Although some natural alternative products are allowed, health problems must be controlled primarily through good management.

- Birds that do become sick cannot be withheld from medical treatment just to preserve their organic status. They should be medicated and then sold into the conventional marketplace.

- Chicken manure must be managed in a way that does not contribute to contamination of crops, soil, or water and that optimizes the recycling of nutrients.

The five freedoms of organic poultry farming

Freedom from hunger and thirst

Laying birds should have freedom from hunger and thirst, with the provision of a ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigor.

Birds in alternative systems tend to be more sensitive to marginal dietary deficiencies than birds in cage systems, and low levels of intake of some key nutrients can predispose the birds to pecking. Diet formulation for birds in alternative systems is a specialist subject, and advice should be sought when necessary from a poultry nutritionist or suitable consultant.

Chickens are not herbivores and do not have the necessary enzymes to digest grass. It is therefore essential that free-range birds are supplied with a well-balanced diet and nutritional deficiencies are prevented.

The importance of water should not be overlooked, as chickens need clean water at all times. Domestic chicken require approximately 40ml of water at one day old, 120ml by 6 weeks of age and 180ml or more once they start laying.

Water and feed dispensers that do not require birds to walk long distances but are at sufficient distance to encourage exercise should be provided. Birds should not have to walk more than 2.5m to drink water.

It is important that water and feed troughs are kept clean of droppings, litter, soil and other contaminants. Feed troughs should be kept clean and dry. They should be emptied and cleaned two or three times per week, or daily if necessary. They should not be washed unless they become contaminated with harmful residues or unless the feed gets wet.

It is important that feed does not get mouldy, as this may lead to the growth of harmful myoctoxin producing fungi, which can cause mortalities.

Water troughs need to be cleaned daily and replaced with fresh water. Efforts should be made to minimize the risk of drinking water freezing.

Freedom from discomfort

Laying birds should have freedom from discomfort that may arise from environmental extremes of temperature, climate, ventilation, dust and gas levels, litter quality and light levels. Organic standards for housing, litter and ventilation should ensure that birds are not at an excessive risk from environmental contamination within the house.

Freedom from pain, injury and disease

Poultry systems should ensure freedom from pain, injury and disease by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment. Animal health management should be based mainly on prevention by means other than the use of preventive allopathic medicines. However, when animals are sick or injured, they should be treated immediately.

Distress, pain and suffering will inevitably result from outbreaks of injurious feather pecking or cannibalism, and good practice should be observed in reducing the incidence of these.

Hock and foot pad lesions (or burns) may occur when litter becomes damp and has high levels of ammonia from faeces. These can be painful and provide an entry point for bacterial infection. Careful management practices should be put in place to avoid wet litter.

Freedom from fear and distress

Freedom from fear and distress should be ensured by providing conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering.

a) Fear

Birds may display fear in response to a variety of different stimuli. Birds reared outdoors may be less prone to panic reactions as they are used to a more varied environment and a wider range of stimuli. However, there are specific fear-inducing factors associated with keeping birds outside. These include panic reactions associated with the fear of predators, the noise of aircraft, the site and sound of approaching.

Free-range birds show less fear of being handled than caged birds, although when exposed to a completely new factor, such as transportation, they are equally frightened. Meat or blood inclusions in eggs can be indicative of fearful birds , although the presence of these is not always related to fear.

Head shaking may be an alerting response of a bird to new or disturbing stimuli, both social and environmental.). It is most commonly observed in larger flocks and in birds of low ranking, although again not always associated with fear.

b) Predation

In their natural state, wild fowl will respond to overhead predation by remaining silent, crouching and freezing, whilst the response to ground predators is to call, run and fly away. The tendency to form groups is also as protection against predators.

Group size can influence the response of birds to predation despite domestication and protection from predators, with larger groups tending to exhibit less anti-predatory behavior.

Other elements of good practice in reducing predation include:

- Feed should be protected and spillage avoided;

- Houses should be located away from shrubs and hedges;

- Dead chickens should be removed and effectively disposed of;

- An overhead shelter should be provided during the daytime;

- Birds should be confined to houses during the hours of darkness and it should be ensured that the houses are secure.

c) Human contact

Sudden movements and changes to routine can induce fear and panic. Panic reactions can lead to injury and, in extreme cases, to suffocation, if large numbers of birds rush to one end of a building as a response to alarm.

Handling of chicks in the first 3 weeks of life has been shown to have a positive impact on production.

d) Good Practice

It is essential that birds are made to feel secure and are not exposed to stressful situations which can lead to panicking. Sudden movement and loud unexpected noise should be avoided, and a good relationship formed with the poultry keeper. Habits form quickly and die hard with poultry. The period immediately after new pullets arrive is crucial and should be used to familiarize the birds with their new environment. This can be done in stages: keep them in to get to know the house, then give access to the outside, and then active encouragement to range (scatter feed). Very often, in large flocks, a considerable percentage can form the habit of never going outside.

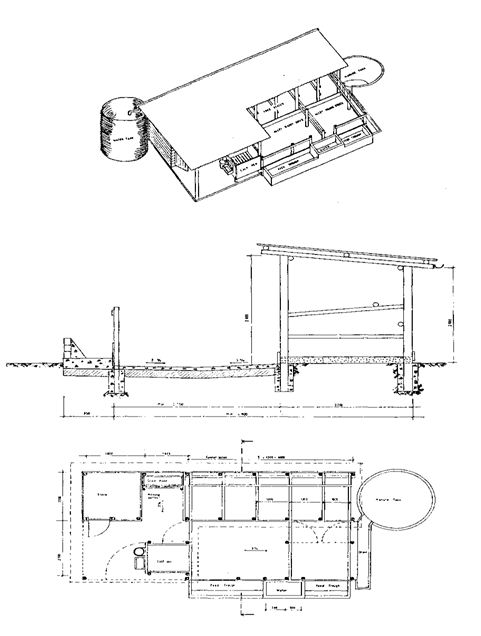

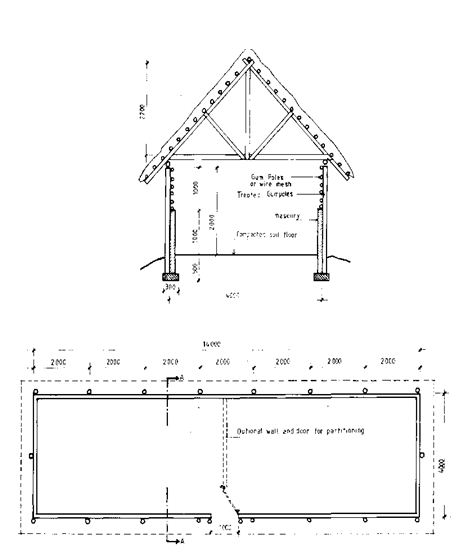

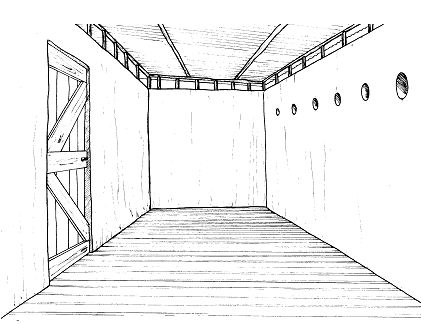

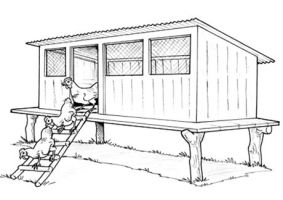

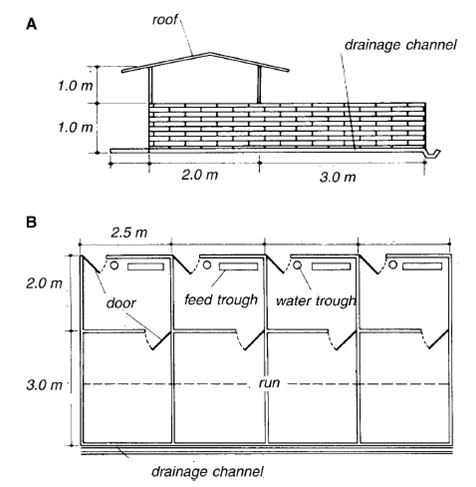

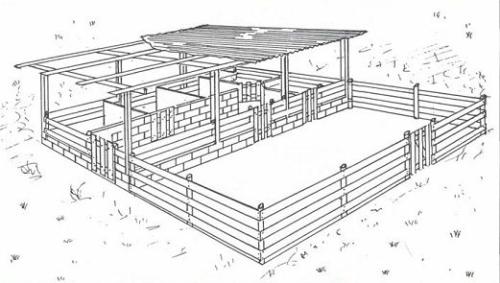

Housing

Buildings for all poultry must meet the following minimum conditions:

- poultry houses must be structures with their own dedicated grazing, air space, ventilation, feed and water;

- at least one third of the floor area shall be solid, that is, not of slatted or of grid construction, and covered with a litter material such as straw, saw dust or sand;

- in poultry houses for laying hens, a sufficiently large part of the floor area available to the hens must be available for the collection of bird droppings;

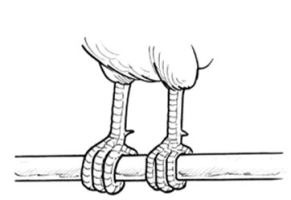

- they must have perches of a size and number commensurate with the size of the group;

- they must have exit/entry pop-holes of a size adequate for the birds, and these pop-holes must have a combined length of at least 4 m per 100 m2 area of the house available to the birds;

- each poultry house must not contain more than:

- the total usable area of poultry houses for meat production on any single production unit, must not exceed 1,600 m2.

4800 chickens, or;

3000 laying hens;

Types of housing

There are two main categories of housing organic poultry: static and mobile.

|

|

|

There are a number of good practice points to be considered in the design of buildings for poultry:

- Provision of dry, friable litter.

- Birds should not need to walk more than 3m to find water and food.

- Avoidance of key areas that can be patrolled by predators.

- No draughts.

- No shafts of light should enter the building.

- Dark areas to be avoided except for nest boxes.

- Vermin-control. Although provision of vermin proof conditions is desirable, this is not really possible to implement under free-range conditions.

- Adherence to housing standards.

- In fixed house situations, either wire mesh or stones in areas immediately outside pop holes.

- Finally and most importantly, air quality (i.e. low ammonia levels, correct humidity, correct temperature and good ventilation) plays a crucial role in health management. The position of a house can influence ranging activity and bird health. Soil type and drainage are instrumental in determining the extent of build up of soil-borne parasites.

- Locating houses on free draining, south facing pasture is preferable in order to minimise the build up of internal parasites and coocidial oocysts and to ensure better retention of grass cover.

- Ideally, houses should be positioned in the centre of the land area so that a series of radiating paddocks can be created around the unit.

- Sitting houses at right angles to the prevailing wind slightly moderates the amount of wind entering the building through the pop holes.

- Accessibility during all weather conditions is an important consideration

- Range areas bordered by dense woodland are likely to be at greater risk from predation by foxes in particular.

Litter management

Litter management is a vital component of managing the welfare of birds as ammonia release from poor litter can lead to conditions such as breast blister, hock burn, pododermatitis and respiratory disease. Management of litter in free range systems presents problems, particularly in winter when the weather is cold and litter is likely to become wet.

Three factors have particularly important effects on litter condition:

Three factors have particularly important effects on litter condition:

- litter moisture,

- greasy capped litter (resulting from too much fat in the feed or feed of poor quality); and

- Nitrogen in the litter.

Perches

The provision of perches for laying birds satisfies a natural behavioral activity. However, if badly designed, these can result in pain and injury. Perches should be arranged so as to enable birds to easily move between them and other equipment, thus reducing the risk of collisions and subsequent bruising and/or other damage. Consideration should be given to minimizing bird stress and downgrading during catching at the end of the laying period. The ability to remove perches aids this process.

| Lighting

In the case of laying hens, natural light may be supplemented by artificial means to provide a maximum of 16 hours of light per day. A continuous period of 8 hours of nocturnal rest without artificial light is required.

Nest Boxes To reduce the impact of excessive aggression within a flock, and to avoid floor laying and wastage, it is important that sufficient nest boxes are available. The provision of perches and of ground-level nest boxes will also encourage the use of nest boxes amongst a greater proportion of hens. It is important that nest boxes are sufficiently accessible so that they can be easily cleaned between batches.

|

|

Pigs

The following issues are most relevant to pig production:

General

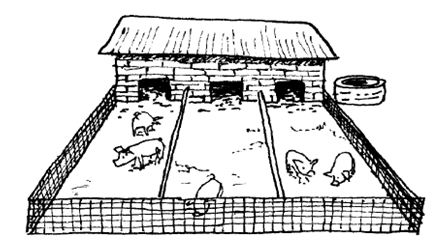

- Livestock production has to be land-based (i.e. livestock forms an integral part of the crop rotation system on the farm; landless livestock production is not acceptable.

- Conventional pigs have to be reared under organic standards for six months before they are considered organic (i.e. the first litter after the conversion period can be sold as organic). Simultaneous conversion of land and livestock is possible as long as most of the feed for the animals comes from the converting farm.

- The choice of breeds or strains should favor pigs that are well adapted to the local conditions and to the husbandry system intended. Vitality and disease resistance are particularly mentioned, and preference should be given to indigenous species.

Origin of animals and conversion

- When an organic herd is constituted for the first time, conventionally reared piglets can be bought at weaning (at less than 25 kg) and reared as organic.

- An established breeding herd can bring in gilts from non-organic holdings to allow for natural growth in the herd to a maximum of 20% of the herd, if organically reared animals are not available. This number of bought-in breeding animals can be increased under special circumstances (major expansion, change of breed, new specialization developed).

- Boars can be brought in from non-organic holdings.

- Livestock brought in from non-organic holdings for breeding purposes cannot be sold as organic either for slaughter or for breeding.

Feeding

|

|

- Disease prevention must be based on breed selection, husbandry, high quality feed, free range conditions allowing regular exercise and appropriate stocking densities;

- Sickness and injury must be treated immediately ;

- Herbal medicine, homeopathy and trace elements and vitamins should be used in preference to chemically synthesized allopathic veterinary medicinal products, but only if they are likely to be effective. Otherwise, allopathic treatments must be used to avoid suffering, under the supervision of a veterinarian. Similarly, statutory disease control measures must be carried out ;

- Preventive use of allopathic medicine and antibiotics, growth promoters and hormonal products to synchronize or induce oestrus are prohibited;

- All treatment with allopathic medicine must be recorded, including diagnosis, duration and statutory withdrawal period and a withdrawal period of twice the statutory withdrawal period must be observed (if no statutory withdrawal period is given, a 48-hour withdrawal must be observed) ;

- If a sow or a boar is treated with more than two courses of allopathic treatments in a year (or a piglet in a lifetime) it loses its organic status and must be reconverted or slaughtered as non-organic (vaccinations, treatments for parasites and statutory disease control measures are not taken into account).

Husbandry

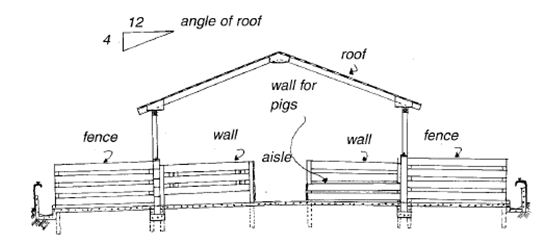

Housing and free-range conditions

|

|

||||||

|

|

Sheep

For more information see here

Breeds

When choosing a breed to raise organically, account must be taken of the capacity of animals to adapt to local conditions; their vitality, and their resistance to disease. In addition, breeds or strains of animals shall be selected to avoid specific diseases or health problems associated with some breeds or strains used in intensive production, and;

Preference is to be given to indigenous breeds and strains.

Use of Indigenous and Local breeds

The emphasis on indigenous breeds may be interpreted as a preference for native and local breeds. The advantage of these, from a health and welfare perspective, is:

- More likely to utilize lower quality feed;

- Being more resilient to climatic stress; and

- Being more resistant to local parasites and diseases.

Selection for disease resistance

One should select for resistance to nematodes and productivity, which may be interpreted as the ewe using resources to fight infection which may have been otherwise used to nurture the lamb.

Purchased animals

Although a closed flock policy is preferable in organic farming, many farms may have to buy-in breeding ewes. The annual allowance for replacement from conventional farms is 10%. Most bought-in ewes arrive in the period between weaning and mating, especially since ewes whose progeny are intended for meat production must be mated on the organic unit, after which they must be managed in accordance with Organic Standards.

Rams may be bought-in for breeding purposes. No conversion period is required, provided the animals are managed in accordance with Organic Standards from the time of arrival on the organic unit. Whilst most breeds of ram are able to mate at any time of the year, the quantity and quality of the ejaculate is better during the ewes' breeding season. The libido of the rams may also be better during this period.

Lambing

The philosophy at lambing should be one of maximum supervision with the minimum of interference. If farmers have to assist a high proportion of ewes (more than 1 in 15-20), then they are interfering unnecessarily or there is some other fault in the management or breeding of the flock. Difficult lambers should be identified, and a decision made whether to retain such animals and their offspring for future breeding.

A ewe should only be assisted at lambing if an examination reveals that she is unlikely to lamb successfully on her own or that further delay may jeopardize the life of the lambs.

Ewes that have been unwell during pregnancy should be quarantined in a separate area for ease of observation.

Ewes that have been unwell during pregnancy should be quarantined in a separate area for ease of observation.

To ensure maximum growth of the placenta and an adequate supply of milk after lambing, it is vital to feed ewes appropriately during mid-pregnancy.

Research has shown that:

- Lambs that are quick to stand and suck after birth have better survival than lambs that are slow to get up and suck.

- Lamb behaviors are influenced by lamb genetics - breed, selection line within breed and sire of the lamb all affected early lamb behaviors. Lamb behavior immediately after birth is heritable, suggesting that selection for lamb behavioral traits could improve lamb vigor at birth and increase lamb survival.

- Lamb rectal temperatures are correlated with lamb behavior. Taking a lambs temperature soon after birth could provide useful information on lamb vigor.

| Housing

Housing is similar to goats. Organic farmers should aim to lamb outside, weather permitting. If a flock already suffers from infectious disease problems, then housing such a flock is likely to magnify the problems as the stocking rates are increased.

Another problem, which has increased over recent years simultaneously with housing, is listeriosis caused by feeding poor quality silage. However, closer observation indoors makes some problems, such as pregnancy toxaemia and hypocalcaemia, easier to detect and treat.

|

|

Review Process

Compiled by Andrew Marete, MSc Animal Genetics, Nov 2011 in collaboration with Infonet

Important link on animal housing: www.fao.org

Information Source Links

- Farmers dairy goat production handbook, farm Africa, (2003)

- Housings Designs for Sheep and Goats; Harold Patterson & Gerald Proverbs, (1988)

Back

Back