The End of the Tetrarchy

Diocletian and his co-emperor Maximian abdicated power on 1 May 305 CE. However, over the course of the next five years, Maximian made several attempts to regain his title, ultimately committing suicide in 310. In the meantime, power had passed to Maximian's son Maxentius and Constantine, the son of a third co-emperor, Constantius.

Unfortunately for Diocletian's legacy and the stability created by the Tetrarchy, a power struggle between the two heirs erupted a year after the former Augustus's abdication. When Constantius died on 25 July 306, his father's troops proclaimed Constantine as Augustus in Eboracum (York, England). In Rome, the favorite was Maxentius, who seized who seized the title of emperor on 28 October 306. Galerius, ruler of the Eastern provinces and the senior emperor in the Empire, recognized Constantine's claim and treated Maxentius as a usurper. Galerius, however, recognized Constantine as holding only the lesser imperial rank of Caesar.

Despite a mutiny against Galerius's co-emperor Severus in 307 and Galerius's subsequent failure to take Rome, Constantine managed to avoid conflict for most of this period. However, by 312, Constantine and Maxentius were engaged in open hostilities, culminating in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, in which Constantine emerged victorious. Although he attributed this victory to the aid of the Christian god, he did not convert to Christianity until he was on his deathbed. The following year, however, he enacted the Edict of Milan, which legalized Christianity and allowed its followers to begin building churches. With the Christian community growing in number and in influence, legalizing Christianity was, for Constantine, a pragmatic move.

Following a rebellion from Licinius, his own co-emperor in 324 CE, Constantine eventually had his former colleague executed and consolidated power under a single ruler. As the sole emperor of an empire with new-found stability, Constantine was able to patronize large building projects in Rome. However, despite his attention to that city, he moved the capital of the empire east to the newly-founded city of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

Arch of Constantine

The Arch of Constantine demonstrates the continuance of the newly-adopted artistic style for imperial sculpture. This arch was erected between the Colosseum and Palatine Hill, the home of the imperial palace. It stands over the triumphal route before it enters the Republican Forum. This forms a dialogue with the Arch of Titus at the top, overlooking the Forum and the Arch of Septimius Severus, which, in turn, stands at the other end of the Forum before the Via Sacra heads uphill to the Capitolium.

Arch of Constantine

Rome, Italy. 315 CE.

The Senate commissioned the triumphal arch in honor of Constantine's victory over Maxentius. It is a triple arch and its iconography represents Constantine's supreme power and the stability and peace brought to Rome by his reign.

The Arch of Constantine is especially noted for its use of spolia, architectural and decorative elements removed from one monument for use on another. Those from the monuments of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius—all considered good emperors of the Pax Romana—were reused as decoration.

Trajanic panels, which depict the emperor on horseback defeating barbarian soldiers, adorn the interior of the central arch. The original face was reworked to take the likeness of Constantine. Eight roundels, or relief discs, adorn the space just above the two smaller side arches. These are Hadrianic and depict images of hunting and sacrifice. The final set of spolia includes eight panel reliefs on the arch's attic, from the era of Marcus Aurelius, depicting the dual identities of the emperor, as both a military and a civic leader. The incorporation of these elements symbolize Constantine's legitimacy and his status as one of the "good emperors."

The rest of the arch is decorated using Late Antique styles. The proximity of different artistic styles, under four different emperors, highlights the stylistic variations and artistic development that occurred, both in the second century CE, as well as their differences to the Late Antique style. Besides decorative elements in the spandrels, a Constantinian frieze runs around the arch, between the tops of the small arches and the bottoms of the roundels. This frieze highlights the artistic style of the period and chronologically depicts Constantine's rise to power. Unlike previous examples of Late Antique art, the bodies in this frieze are completely schematic and defined only by stiff, rigid clothes. In one scene, featuring Constantine distributing gifts, the emperor is centrally depicted and raised above his supporters on a throne .

Detail of northern frieze of the Arch of Constantine

Detail of Constantine distributing gifts, Rome, Italy. Marble. 312-315 CE.

Basilica Nova and the Colossus of Constantine

When Constantine and Maxentius clashed at the Milvian Bridge, Maxentius was in the middle of building a grand basilica, eventually renamed the Basilica Nova, near the Roman Forum. The basilica consisted of one side aisle on either side of a central nave.

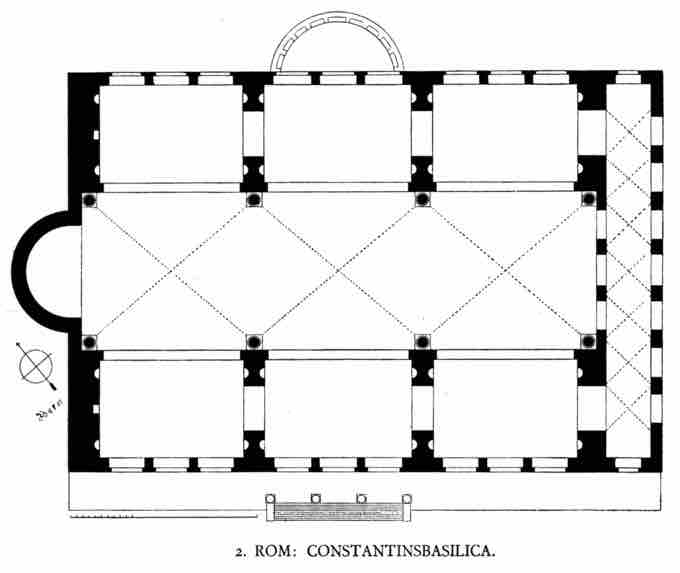

Ground plan

Basilica Nova, Rome

When Constantine took over and completed the grand building, it was 300 feet long, 215 feet wide, and stood 115 feet tall down the nave. Concrete walls 15 feet thick supported the basilica's massive scale and expansive vaults. It was lavishly decorated with marble veneer and stucco. The southern end of the basilica was flanked by a porch, with an apse at the northern end.

Basilica Nova

As it stands today in Rome, Italy.

The apse of the basilica Nova was the location of the Colossus of Constantine. This colossus was built from many parts. The head, arms, hands, legs, and feet were carved from marble, while the body was built with a brick core and wooden framework and then gilded.

Head of the Colossus of Constantine

Marble, Rome, Italy

Only parts of the Colossus remain, including the head that is over eight feet tall and 6.5 feet long. It shows a portrait of an individual with clearly defined features: a hooked nose, prominent jaw, and large eyes that look upwards. Like the porphyry bust of Galerius, Constantine's portrait combines naturalism in his nose, mouth, and chin with a growing sense of abstraction in his eyes and geometric hairstyle. He also held an orb and, possibly, a scepter, and one hand points upwards towards the heavens. Both the immensity of the scale and his depiction as Jupiter (seated, heroic, and semi-nude) inspire a feeling of awe and overwhelming power and authority.

The basilica was a common Roman building and functioned as a multi-purpose space for law courts, senate meetings, and business transactions. The form was appropriated for Christian worship and most churches, even today, still maintain this basic shape.

Rome after Constantine

Following Constantine's founding of a "New Rome" at Constantinople, the prominence and importance of the city of Rome diminished. The empire was then divided into east and west. The more prosperous eastern half of the empire continued to thrive, mainly due to its connection to important trade routes, while the western half of the empire fell apart. While at times over the next several centuries, Byzantium controlled Italy and the city Rome, for the most part the Western Roman Empire, due to being less urban and less prosperous, was difficult to protect. Indeed, the city of Rome was sacked multiple times by invading armies, including the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, over the next century.

The multiple sackings of Rome resulted in the raiding of the marble, façades, décor, and columns from monuments and buildings throughout the city. Parts of ancient Rome, especially the Republican Forum, returned once again to the cow pastures that they originally were at the time of the city's founding, as floods from the Tiber washed them over in debris and sediment.

Constantinople

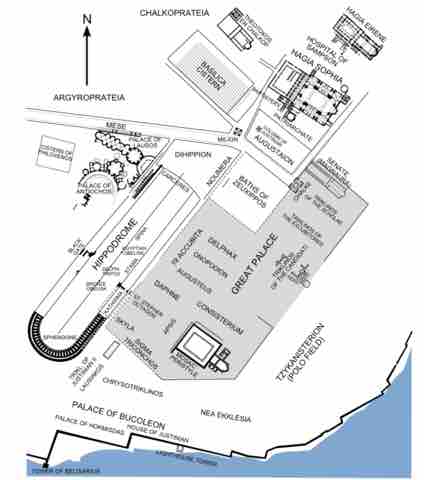

Constantine laid out a new square at the centre of old Byzantium, naming it the Augustaeum. The new senate-house was housed in a basilica on the east side. On the south side of the great square was erected the Great Palace of the Emperor with its imposing entrance and its ceremonial suite known as the Palace of Daphne. Nearby was the vast Hippodrome for chariot races, seating over 80,000 spectators, and the famed Baths of Zeuxippus. At the western entrance to the Augustaeum was the Milion, a vaulted monument from which distances were measured across the Eastern Roman Empire.

Imperial district of Constantinople

Present-day Istanbul, Turkey. Begun 320 CE.

From the Augustaeum led a great street, the Mese, lined with colonnades. As it descended the First Hill of the city and climbed the Second Hill, it passed on the left the Praetorium or law-court. Then it passed through the oval Forum of Constantine where there was a second Senate-house and a high column with a statue of Constantine in the guise of Helios, crowned with a halo of seven rays and looking toward the rising sun. From there the Mese passed on and through the Forum Tauri and then the Forum Bovis, and finally up the Seventh Hill (or Xerolophus) and through to the Golden Gate in the Constantinian Wall.

The Aula Palatina, Trier

Constantine built the Aula Palatina (c. 310 CE) as a part of the palace complex. Originally it was attached to smaller buildings (such as an antehall, a vestibule, and service buildings) attached to it. The Aula Palatina has a simplified Roman basilican plan, consisting of a wide nave that ends in a north-facing apse. Although round arches repeat throughout the interior and exterior, the building deviates from the traditional basilica with the flat ceiling that covers the nave and the flat roof that tops the apse.

Aula Palatina, exterior.

Known today as the Church of the Redeemer Trier, Germany. c. 310 CE.

Aula Palatina, interior.

Known today as the Church of the Redeemer Trier, Germany. c. 310 BCE.