|

Tamarind

Scientific name:

Tamarindus indica

Order/Family:

Fabales: Fabaceae

Local names:

Swahili: Ukwaju, Mkwayo

|

| General Information and Agronomic Aspects | Medicinal Properties and Uses | |||

| Information on Pests and Diseases | Information Source Links |

General Information and Agronomic Aspects

|

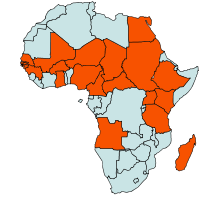

| Geographical Distribution of Tamarind in Africa |

The fruit is edible and can also be used as a sort of spice to be added to food. Young leaves and very young seedlings and flowers are cooked and eaten as greens and in curries in India. In Zimbabwe, the leaves are added to soup and the flowers are an ingredient in salads. Tamarind seeds have been used in a limited way as emergency food. They are roasted, soaked to remove the seed-coat, then boiled or fried, or ground to a flour or starch (Morton 1987).

Climatic conditions, soil and water management

Tamarind is well adapted to semi-arid tropical conditions It also grows well in many humid tropical areas with seasonally high rainfall. It grows well over a wide range of soil and climatic conditions, occurring in low-altitude woodland, savannah and bush, often associated with termite mounds. It grows in well-drained, slightly acidic soils and although it cannot withstand stagnant inundation, it can tolerate a wide range of physical site characteristics. It prefers semi-arid areas and wooded grassland, and can also be found growing along stream and riverbanks. It does not penetrate into the rainforest. Its extensive root system contributes to its resistance to drought and wind. It also tolerates fog and saline air in coastal districts, and even monsoon climates, where it has proved its value for plantations.Young trees are killed by the slightest frost, but older trees seem more cold resistant than mango, avocado or lime. A long, well-marked dry season is necessary for fruiting (EcoPort).

Propagation and planting

The tamarind becomes a fairly large tree, so keep this in mind when planting the tree. It should be planted in sunny areas. It is highly wind-resistant with strong, supple branches. It may be propagated from seeds, and vegetatively by marcotting (air layering), grafting and budding. Root stocks are propagated from seed, which germinate within a week. Seeds retain their viability for several months if kept dry. Plant seeds 1 to 1.5 cm deep in containers. Seeds should be selected from viable trees with good production and quality. Germination is best when seeds are covered by 1.5 cm loose, sandy loam or by a mixture of loam and sand. Seedlings should attain at least 80 cm before being transplanted to their final location at the beginning of the rainy season. Trees begin to produce fruit in 6 to 8 years.

Outstanding mother trees are vegetatively propagated; shield and patch budding and cleft grafting are fast and reliable methods, currently used in large-scale propagation in the Philippines. Trees can also be propagated from branch cuttings, and superior clones can also be grafted onto seed-propagated rootstock. Vegetatively propagated trees come into bearing within 3 to 4 years. They produce more fruits as well as more-uniform fruits than seed propagation. Trees also seem to remain smaller - making them easier to harvest and handle (ICRAF, CRFG; Lost Crops of Africa). Young trees should be planted in large holes to accommodate the root system. They should be planted slightly higher than ground level to allow for subsequent settling of the soil and a water basin should be built around each tree to assure adequate moisture for young trees. (Morton 1987)

Husbandry

Young trees are pruned to allow 3 to 5 well spaced branches to develop into the main scaffold structure of the tree. Maintenance pruning only is required after that to remove dead or damaged wood (CRFG).

Information on Pests and Diseases

Medicinal Properties and Uses

In the Sahel, the fruit pulp is used primarily for sauces, porridge and juice. In eastern and western Africa, the fruit pulp is eaten raw, but local varieties generally have a strong acidic taste compared with sweet-tasting cultivars introduced from Thailand. In Kenya, the fruit pulp is also used to tenderise meat (Kalinganire et al. 2007).

The fruit pulp has laxative properties and is highly nutritive. It is often added to boiled cereal pap for the treatment of constipation. In China it is dispensed to treat nausea during pregnancy. (Iwu 1993). Tamarind preparations are universally recognised as refrigerants in fevers and as laxatives and carminatives (induce the expulsion of gas from the stomach or intestines). Alone, or in combination with lime juice, honey, milk, dates, spices or camphor, the pulp is considered effective as a digestive, even for elephants, and as a remedy for biliousness and bile disorders, and as an antiscorbutic. The pulp is said to aid the restoration of sensation in cases of paralysis (Morton. 1987).

Roots: It northern Nigeria, the roots are used for leprosy treatment. In many parts of West Africa, a decorction of the roots is the principal ingredient in remedies for cardiac diseases (Iwu 1993).

Leaves: Tamarind leaves and flowers, dried or boiled, are used as poultices for swollen joints, sprains and boils. Lotions and extracts made from them are used in treating conjunctivitis, as antiseptics, as vermifuges, treatments for dysentery, jaundice, erysipelas (a skin infection that often follows strep throat) and hemorrhoids and various other ailments (Morton 1987).

Bark: The bark of the tree is regarded as an effective astringent, tonic and febrifuge. Fried with salt and pulverised to an ash, it is given as a remedy for indigestion and colic. A decoction is used in cases of gingivitis and asthma and eye inflammations; and lotions and poultices made from the bark are applied on open sores and caterpillar rashes (Morton 1987). The bark infusion is drunk by woman after childbirth as a general tonic (Iwu 1993).

Seeds: The seeds are a rich source of protein, and have a favourable amino acid composition. The powdered seeds are made into a paste for treating boils and, with or without cumin seeds and palm sugar, are prescribed for chronic diarrhoea and dysentery (Kalinganire et al., Morton 1987).

Tamarind is also a valuable timber species, used in making furniture, tool handles and charcoal and as fuelwood (Kalinganire et al.2007).

Information Source Links

- Bekele-Tesemma, B. (2007). Useful trees and shrubs for Ethiopia. World Agroforestry Centre, Nairobi, Kenya. ISBN 92-9059-2125 www.worldagroforestry.org

- CRFG California Rare Fruit Growers www.crfg.orgl

- ECHO Plant Information Sheet. (2006). TAMARIND.www.echocommunity.org

- EcoPort, the consilience engine. www.ecoport.org

- ICRAF The World Agroforestry Centre. Agroforestry Tree Database. A tree species reference and selection guide- Tamarindus indica. www.worldagroforestry.org

- Iwu, M. M. (1993). Handbook of African Medicinal Plants. CRC PressConsumer . ISBN 084934266X

- Kalinganire, A.; Weber, J.C.; Uwamariya, A. and Kone, B. (2007) Improving Rural Livelihoods through Domestication of Indigenous Fruit Trees in the Parklands of the Sahel. World Agroforestry Centre. Fruit trees Ch 10 4/9/07 13:55 Page 186 www.worldagroforestrycentre.org

- Lost Crops of Africa. Volume III. Fruits (2008). National Research Council. National Academies Press. ISBN: 978-0309105965 download

- Maundu, P. and Tengnäs, B. (2005). Useful trees and shrubs for Kenya. World Agroforestry Centre. ISBN: 9966-896-70-8

www.worldagroforestry.org - Morton, J. F. (1987). Fruits of Warm Climates. Miami, FL. ISBN: 0-9610184-1-0. Distributed by Creative Resource Systems, Inc. Box 890, Winterville, N.C. 28590 ISBN 978-0961018412 www.hort.purdue.edu

- Plant Cultures. Exploring plants and people. www.kew.org

Back

Back