ARTH101 Study Guide

Unit 1: Defining Art

1a. Distinguish between the form and content of an artwork

- How does art address our senses and minds differently?

- What aspects of art can be analyzed comparatively regardless of which artist or culture produced it?

- What shapes our interpretation of art?

Broadly, our understanding of art and how we explain it consists of a few qualities. First are the descriptions and analyses of a work of art's features. Those are either based on the perceptual qualities of the artwork (such as the colors, shapes or contrasts employed in the composition), as well as the material they're made of and the methods used to produced them. Second, there are interpretive aspects that are informed by culture, and these interpretations can be unique to a given person, group, or society. Since humans perceive art very similarly across most populations (by using their eyes and ears), there can be quite broad agreement as to the perceptual and material aspects of art, since these can be objectively verified.

However, interpretations of art can be also be subjective. Art is often controversial, mysterious, socially significant, or personal. These interpretations depend on other factors, such as the cultural background of the artist or viewer, the use of symbolic material, or the artistic consumption habits of its audience. The perceptual and material dimensions (the objective aspects) of an artwork are described as its "form", whereas the interpretive (subjective) components are its "content". These categories, form and content, derive from Greek antiquity, where philosophers made the distinction between what something says (the content), and how something is said (its form).

Example:

In this image, a formal aspect of the image is that it is a triptych, meaning an image composed out of three frames aligned side-by-side. An aspect of content is that one needs to know something about important figures in Christianity as the image depicts, in order of left to right: John the Baptist, the Virgin Mary, Jesus, St. John the Evangelist, and Mary Magdalene.

To review, read Form and Content.

1b. Explain aesthetics and the role it plays in different cultural conventions and perspectives

- What field of general intellectual endeavor does aesthetics belong to?

- What kinds of questions are asked by aesthetics?

- How does on articulate aesthetic insights?

It is hard to separate art from conversations about it, which are also called the "discourses" of art. Art is saturated with concepts, histories, schools and movements, linkages to the history of ideas, debates about the nature of beauty, or judgements as to what makes art "good" or 'bad". Aesthetics is a branch of philosophy that deals with matters related to art. The term is based on the ancient Greek word aisthesis, which means "sensory experience". As you might expect, different cultures have produced different discourses on aesthetics: for example, what might be considered beautiful in Indian art 500 years ago is likely going to be very different from what was considered beautiful in the European Renaissance or in a 20th-century postmodern exhibit. The development of ideas is inextricably linked to the movements of culture, and aesthetics is affected by variations across social geographies and throughout history.

Example:

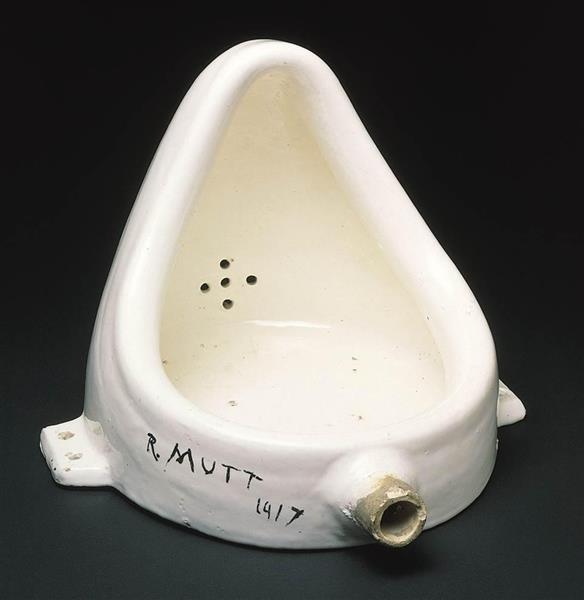

A famous artwork that explicitly challenged conceptions as to what can be considered art was Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, which was an ordinary urinal which he signed 'R. Mutt.' Duchamp attempted to exhibit Fountain at a show produced by Society of Independent Artists in order to test the limits of the society’s principles and commitment to artistic freedom.

To review, read Defining Art.

1c. Explain the difference between subjective and objective responses to art

- What kinds of statements about art are likely to be non-controversial?

- Which aspects of art require a more personal response?

- What aspects of art can be subject to scientific investigation?

The distinction between subjective and objective information is key to the development of science and the philosophies emerging in the Enlightenment. Both concepts are from the philosophy of Descartes, who was famous for stating "I think, therefore I am". We come to know the objective dimension of the world through our senses, and through instruments that measure our environment. For example, one can analyze the pigments used in cave paintings and arrive at objective determinations about when they were produced using methods like carbon dating. Even in a less technical sense, we can agree that certain stylistic features belong to particular periods of time. The subjective dimension is less tangible, and is rooted in personal experiences. We do not only encounter art as raw sensory data, but we come to it already influenced by our own biases, expectations, needs, and prior art education. These factors, as well as the other aspects that make us individuals, play a role in shaping our personal and social subjective responses to a work of art.

Example:

An example of subjective and objective dimensions playing out in art can be found in a story related to Andy Warhol's work Brillo Soap Pads (also called the Brillo Box). Andy Warhol designed a series of plywood boxes and hired carpenters to create replicas of mass produced commercial goods, including a replica box of Brillo soap pads that looked identical to the actual commercial product. Objectively the artwork is just a cardboard box made to look like a common store item of packaged goods. But subjectively, the work invokes the graphic style of popular consumer culture and in an art context, can become quite valuable to collectors of art. This work was bought in 1969 for $1000, and sold at Christie's in 2010 for $3 million! Aside from it's monetary value, another aspects of its subjective dimension is the way that it makes its audience reconsider the potential aesthetic value of products they would never consider to be artistic in the first place.

To review, read Subjective and Objective Perspectives.

1d. Define the categories of art, such as fine art, pop art, and decorative art

- What are some of the major kinds of popular art?

- What arts are usually categorized under the concept of fine art?

- How is decorative art different from popular and fine art?

Taking a broad view of the diversity of art practices, we can easily note that there is art that is "in the museums" (like paintings and sculptures), which is different from art that we may find "on the streets" (like graffiti or billboards) or even "on our persons" (as in the case of fashion) or in our homes (such as with embroidery and rugs). Similarly, art can be organized into the categories of fine art, popular art, or decorative art, depending on the roles that it fulfills along these social dimensions. A work of art can be considered important for cultural preservation and reflection (fine art), to be a kind of popular communication (pop art), or to serve as a handicraft that ornaments or decorates the useful items of our lives (decorative art).

Example:

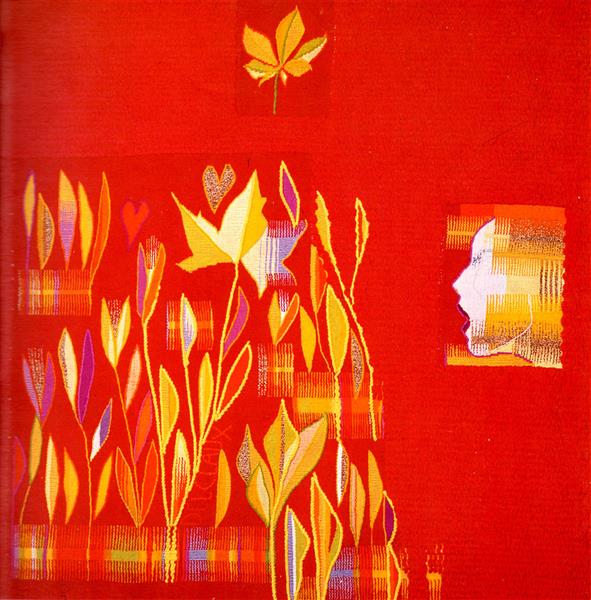

Some artworks intentionally blur the lines between functional decorative and fine art sensibilities, producing objects that seem potentially usable in everyday contexts, but intended for ultimately only for gallery exhibition, such as Rodrigo Franzao's Mind I.

Andy Warhol's Brillo Box (discussed earlier) is a good example of pop art, which is fine art inspired by popular culture. So these categories of popular, fine and decorative arts can certainly overlap with each other and even cross-pollinate.

To review, read Artistic Categories.

1e. Recognize, describe, and evaluate artistic styles, such as naturalistic, abstract, and non-objective

- What does it mean to say that art may be "representational"?

- How much stylization might be apparent in art before it is considered to be abstract?

- What kinds of aesthetic experiences are produced by non-objective art?

We often expect art to depict something specific, as when a portrait needs to resemble a particular person. This is art's 'mimetic' role, which comes from the Greek word mimesis and refers to creating a representation of something. But we also know that art often takes great creative liberties in representation, and that many works impart all strong stylizations to the objects they represent. These artworks are called "abstractions", since their main goal is not to produce an "accurate" mimesis. Finally, we have all experienced works of art that do not resemble anything at all from our everyday experience. This kind of art may work with geometries, colors, or materials in ways that do not lend themselves to a clear interpretation. This kind of art is called "non-objective", because it foregoes any ties to recognizable objects of our experience.

Example:

Carles Delclaux's Nura is an example of abstract art, because it depicts recognizable objects in a highly stylized and thus non-naturalistic manner.

To review, read Artistic Styles.

Unit 1 Vocabulary

Be sure you understand these terms as you study for the final exam. Try to think of the reason why each term is included.

- subjective

- objective

- form

- content

- aesthetics

- fine art

- pop art

- decorative art

- abstractions

- non-objective

- non-naturalistic