|

Citrus plants

Scientific name:

Citrus spp.

Family:

Rutales: Rutaceae

Local names:

Swahili: Machungwa (oranges), Ndimu (limes), Limau (lemons), Madanzi (grapefruits), Chenza (tangerines/mandarins)

Pests and Diseases: African citrus psyllid

Anthracnose

Ants

Aphids

Citrus blackfly

Citrus bud mite

Citrus rust mite

Citrus tristeza virus

Damping-off diseases

Dodder

False codling moth

Fruit flies

Greening disease

Leafmining caterpillars

Mealybugs

Phaeoramularia fruit and leaf spot

Phytophthora-induced diseases

Red fire or weaver ants

Root-knot nematodes

Scales

Sedges

Swallowtail butterfly

Termites

Thrips

Whiteflies

Termites, Couch grass, Citrus woolly whitefly

|

|

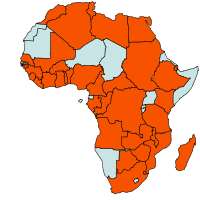

| Geographical Distribution of Citrus plants in Africa |

- Sweet oranges (Citrus sinensis)

- Limes (C. aurantifolia)

- Grapefruits (C. paradisi)

- Lemons (C. limon)

- Mandarins (C. reticulata). These are often called tangerines.

Citrus varieties of commercial importance include the following:

- Oranges: 'Washington Navel' (alt: 1000-1800 m above sea level), 'Valencia Late', 'Hamlin' and 'Pineapple' (all alt from 0 - 1500 m above sea level)

- Mandarins: 'Kara', 'Satsuma' (0-1500 m above sea level), 'Clementine', 'Dancy' (0-1800 m above sea level), 'Pixie', 'Encore' and 'Kinnow'

- Tango/ Tangelo (hybrids of mandarins): 'Temple' a Tango (mandarin x orange) and 'Minneola' a Tangelo (mandarin x grapefruit)

- Grapefruit: 'Marsh Seedless', 'Duncan' and 'Ruby Red', 'Red Blush' (0-1500 m above sea level) and 'Thomson' (1000-1500 m above sea level)

- Lemons: 'Meyer', 'Eureka', 'Lisbon' and 'Villa Franca' (1000-1500 m above sea level), Rough lemon (0-1500 m)

- Limes: 'Mexican', 'Tahiti' and 'Bears' (0-1500 m)

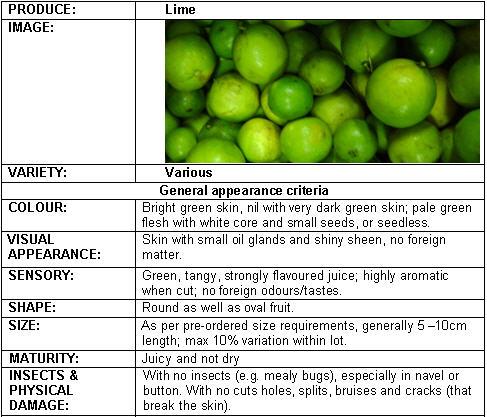

Nutritive value per 100 g of edible portion

| Raw or Cooked Citrus | Food Energy (Calories / %Daily Value*) |

Carbohydrates (g / %DV) |

Fat (g / %DV) |

Protein (g / %DV) |

Calcium (g / %DV) |

Phosphorus (mg / %DV) |

Iron (mg / %DV) |

Potassium (mg / %DV) |

Vitamin A (I.U) |

Vitamin C (I.U) |

Vitamin B 6 (I.U) |

Vitamin B 12 (I.U) |

Thiamine (mg / %DV) |

Riboflavin (mg / %DV) |

Ash (g / %DV) |

| Lemon raw | 29.0 / 1% | 9.3 / 3% | 0.3 / 0% | 1.1 / 2% | 26.0 / 3% | 16.0 / 2% | 0.6 / 3% | 138 / 4% | 22.0 IU / 0% | 53.0 / 88% | 0.1 / 4% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 3% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.3 |

| Lime raw | 30.0 / 2% | 10.5 / 4% | 0.2 / 0% | 0.7 / 1% | 33.0 / 3% | 18.0 / 2% | 0.6 / 3% | 102 / 3% | 50.0 IU / 1% | 29.1 / 48% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.3 |

| Orange raw | 47.0 / 2% | 11.7 / 4% | 0.1 / 0% | 0.9 / 2% | 40.0 / 4% | 14.0 / 1% | 0.1 / 1% | 181 / 5% | 225 IU / 4% | 53.2 / 89% | 0.1 / 3% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 6% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.4 |

| Grapefruit pink raw | 42.0 / 2% | 10.7 / 4% | 0.1 / 0% | 0.8 / 2% | 22.0 / 2% | 18.0 / 2% | 0.1 / 0% | 135 / 4% | 1150 IU / 23% | 31.2 / 52% | 0.1 / 3% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 3% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.4 |

| Grapefruit white raw | 33.0 / 2% | 8.4 / 3% | 0.1 / 0% | 0.7 / 1% | 12.0 / 1% | 8.0 / 1% | 0.1 / 0% | 148 / 4% | 33.0 IU / 1% | 33.3 / 56% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 2% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.3 |

Temperature plays an important role in the production of high quality fruit. Typical colouring of fruit takes place if night temperatures are about 14° C coupled with low humidity during ripening time. Exposure to strong winds and temperatures above 38° C may cause fruit drop, scarring and scorching of fruits. In the tropics the high lands provide the best night weather for orange colour and flavour.

Depending on the scion/ rootstock combination, citrus trees grow on a wide range of soils varying from sandy soils to those high in clay. Soils that are good for growing are well-drained, medium-textured, deep and fertile. Waterlogged or saline soils are not suitable and a pH range of 5.5 to 6.0 is ideal. In acidic soil, citrus roots do not grow well, and may lead to copper toxicity. On the other hand at pH above 6, fixation of trace elements take place (especially zinc and iron) and trees develop deficiency symptoms. A low pH may be corrected by adding dolomitic lime (containing both calcium and magnesium)

|

| © University of Hawaii, www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/nelsons/Misc/ |

A citrus orchard needs continuous soil moisture to develop and produce, and water requirement reaches a peak between flowering and ripening. However, many factors such as temperature, soil type, location, plant density and crop age influence the quantity of water required. Well-distributed annual rainfall of not less than 1000 mm is needed for fair crop. In most cases, due to dry spells, irrigation is necessary. Under rain-fed conditions, flowering is seasonal.

There is a positive correlation between the onset of a rainy season and flower break. With irrigation flowering and picking season could be controlled by water application during dry seasons. Irrigation systems involving mini sprinklers irrigating only soil next to citrus trees have been developed as an efficient and water conserving irrigation method.

Citrus rootstocks have the following characteristics:

-

Rough lemon (C. jambhiri)

Seedlings produce a uniform and fast growing rootstock, which is easy to handle in the nursery. The plant develops a shallow but wide root system with a vigorous taproot. Trees budded on rough lemon produce an early, good yield but the fruit quality especially during the first years is not satisfactory. Trees are comparatively short-lived. Rough lemon prefers deep, light soil and do not tolerate poor drainage or waterlogging. It is tolerant to citrus tristeza virus but susceptible to Phytophthora spp., citrus nematodes and soil salinity. It is drought tolerant. Rough lemon can be budded with oranges, mandarins, lemons, limes and grapefruits. It is the most commonly used rootstock in East Africa. -

Cleopatra mandarin (C. reticulate)

It is suited to soils of heavier texture. On this rootstock, trees are slow growing with low yields in early years. Trees are long-lived. Its influence on fruit quality is good. It is tolerant to soil salinity. It is susceptible to poor drainage, Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits. -

Citrus trifoliate (Poncirus trifoliate)

It is a dwarfing stock and is most suitable for heavy and less well-drained soils. Rootstock propagation is slow, but budded trees yield heavily and produce high quality fruits. The plants develop abundant roots and often several taproots, which penetrate the soil deeply. It should not be used in calcareous soils. It is tolerant to Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits. -

Carrizo / Troyer citrange (P. trifoliate x C. sinensis)

Rootstocks are somehow difficult to establish. In order to promote fibre roots, young plants should be undercut as long as they are in the seedbed. Citranges are not suitable for very light and strongly alkaline soils. They are sensitive to overwatering but once established produce high quality fruits. They are somehow tolerant to Phytophthora spp. and citrus tristeza virus but susceptible to Exocortis viroid and citrus nematodes. They can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits. -

Citrumelo (P. trifoliate x C. paradise)

Plants produce an expansive root system and therefore have good drought tolerance. They can be used on a wide range of soils and produce an outstanding quality of fruit. They are tolerant to Phytophthora spp. but susceptible to citrus nematodes. They can be budded .oranges, tangarines and grapefruit. -

Rangpur lime(C. aurantifolia)

This stock is suitable for various soil types, including deep sand. It prefers warm locations. It produces vigorous, well-bearing trees with a high degree of drought resistance. It is susceptible to Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges and grapefruits. -

Sweet orange(C. sinensis)

This rootstock produces large and vigorous trees and is suitable for light to medium soils, which are well drained. It produces good quality fruits and the trees are long-lived. It has low drought tolerance and is very susceptible to Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits. -

Sour orange (C. aurantium)

An excellent rootstock in locations where citrus tristeza virus is not a problem since it is very susceptible to the disease. It is tolerant to poor drainage. It has low tolerance to drought. It produces very good quality fruits. It is tolerant to Phytophthora spp. but susceptible to citrus nematodes. It can be buddedwith oranges and grapefruits.

- Select seeds from healthy mother trees for rootstocks

- Hot water treat seeds at 50° C for 10 minutes

- Seeds perform better when planted soon after they are extracted

- Sow seeds in seedbeds or polybags (18x23 cm). Seeds germinate in 2 to 3 weeks

- Water the seeds regularly, preferably twice a day until they germinate

- Seedlings are normally ready for budding when reaching pencil thickness or 6 to 8 months after germination.

- T-budding is the most common method.

- Do budding during warm months. Avoid budding during cold periods and during dry conditions

- Budded plants are ready for transplanting 4 to 6 months after budding

- Alternatively, obtain budded plants from a registered fruit nursery. These budded plants should be ready for transplanting in the field.

Transplanting in the field

- Transplant in the field at onset of rains.

- Clear the field and dig planting holes 60 x 60 x 60 cm well before the onset of rains.

- At transplanting use well-rotted manure with topsoil.

- Spacing varies widely, depending on elevation, rootstock and variety. Generally, trees need a wider spacing at sea level than those transplanted at higher altitudes. Usually the plant density varies from 150 to 500 trees per ha, which means distances of 4 x 5 m (limes and lemons), 5 x 6 m (oranges, grapefruits and mandarins) or 7 x 8 m (oranges, grapefruits and mandarins). In some countries citrus is planted in hedge rows.

- It is very important to ensure that seedlings are not transplanted too deep.

- After transplanting, the seedlings ought to be at the same height or preferably, somewhat higher than in the nursery.

- Under no circumstances must the graft union ever be in contact with the soil or with mulching material if used.

Tree management / maintenance

- Keep the trees free of weeds.

- Maintain a single stem up to a height of 80-100 cm.

- Remove all side branches / rootstock suckers.

- Pinch or break the top branch at a height of 100 cm to encourage side branching.

- Allow 3-4 scaffold branches to form the framework of the tree.

- Remove side branches including those growing inwards.

- Ensure all diseased and dead branches are removed regularly.

- Careful use of hand tools is necessary in order to avoid injuring tree trunks and roots. Such injuries may become entry points for diseases.

- As a general rule, if dry spells last longer than 3 months, irrigation is necessary to maintain high yields and fruit quality. Irrigation could be done with buckets or a hose pipe but installation of some kind of irrigation system would be ideal. [listitemCitrus is under irrigation in the major citrus world producing countries.[/listitem]

Manure and fertiliser

For normal growth development (high yield and quality fruits), citrus trees require a sufficient supply of fertiliser and manuring. No general recommendation regarding the amounts of nutrients can be given because this depends on the fertility of the specific soil. Professional, combined soil and leaf analyses would provide right information on nutrient requirements.

In most cases tropical soils are low in organic matter. To improve them at least 20 kg (1 bucket) of well-rotted cattle manure or compost should be applied per tree per year as well as a handful of rockphosphate. On acid soils 1-2 kg of agricultural lime can be applied per tree spread evenly over the soil covering the root system. Application of manure or compost makes (especially grape-) fruits sweeter (farmer experience).

Nitrogen can be supplied by intercropping citrus trees with legume crops such as mucuna, cowpeas, clover or dolichos beans, and incorporating the plant material into the soil once a year. Mature trees need much more compost/well rotted manure than young trees to cater for more production of fruit.

Conventional fertilisation depend on soil types, so it is recommended to consult the local agricultural office.

- Plant the windbreak as close as possible and at right angles to prevailing winds.

Symptoms of mineral deficiency

| Nutrient Element | Leaves | Fruit | Tree growth |

| Nitrogen | Pale yellow to old ivory | Reduced crop | Reduced. May produce abundant bloom. Flower buds may fall without opening |

| Phosphorous | Small, dull | Reduced crop. Large. Puffy, bumpy surface, enlarged core cavity and thick rind. |

Reduced |

| Magnesium | Yellow mottling along margin Developing a green wedge to "Christmas tree" pattern. Eventual complete yellowing and defoliation. |

Reduced crop | Reduced |

| Iron | Yellow veins, remain green until final stage of general chlorosis. Reduced size |

Reduced crop | Eventually reduced |

| Zinc | Mottled yellow between main veins. Small narrow Early fall. Reduced size |

Reduced crop, some pale yellow off types |

Eventually reduced |

| Manganese | Normal green along main veins. Rest of leaf pale green to light yellow |

Reduced crop | Eventually reduced |

| Potassium | Old leaves curl and loose their green colour | Small, smooth, thin rind, drop prematurely |

Reduced |

| Copper | Deep green, oversized, then darkened | Splitting and gumming. Dark brown gum soaked eruptions. May turn black. Gum in centre core |

Twigs enlarge at nodes, blister and die back. Gum pockets. "Cabbage head" growth |

Intercropping

Intercropping with shallow rooted crops such as vegetables, herbs, green manure legumes sweet potatoes etc, is recommended in order to keep the soil cultivated around citrus trees.

- Harvest fruits when they are mature. Mature fruits change colour where night temperature is about 14°C coupled with low humidity

- In low altitude areas where fruits remain green, it is necessary to test a few fruits for maturity

- Harvest fruits using a sharp knife, taking care not to bruise the fruits

- Fruits can also be plucked. However, plucking causes the stem to break close to the fruit thus increasing the chance of it being infected

- Wash, sort and grade fruits under shade. Washing water must be clean or treated

- Discard deformed and infected fruits

- Pack fruits in aerated containers for transport to the market

|

| © S. Kahumbu, Kenya |

Indirect Control Methods:

- Promotion of beneficial insects and plants by habitat management: organic orchard design, ecological compensation areas with hedges, nesting sites etc.

- Soil management: Organic compost and plant slurry to improve soil structure and soil microbial activity

- Pruning: : to remove died and diseased shoots/twigs and to provide good aeration of the trees

Direct Control Methods:

- Biological control: release of antagonists, natural predators and entomophagous fungi.

- Mechanical control methods.

- Organic pest and disease control products.

In some cases, preventive and bio-control measures are not sufficient and the damage by a pest or a disease may reach a level of considerable economic loss. This is when direct control measures with natural pesticides, such as pyrethrum, derris, neem, soaps, mineral and plant oil as well as mass trapping and confusion techniques may become appropriate.

Scales

Scales are small insects (1.0 to 7 mm long), which resemble shells glued to the plant. There are many species (types) of scales on citrus, which vary in shape (round to oval) and colour according to the species.

There are two main groups: hard (armoured) and soft (naked). The armoured scales are the most serious pests.

The most important armoured scales attacking citrus are the red scale (Aonidiella aurantii), the mussel purple scale (Lepidosaphes beckii), and the circular scale (Chrysomphalus aonidum).

The most important soft scales are the soft brown scale (Coccus hesperidum) and the soft green scale (Coccus viridiis or C. alpinus).

Female scales have neither wings nor legs. Females lay eggs under their scale. Some species give birth to young scales directly. Once hatched, the tiny scales, known as crawlers, emerge from under the protective scale. They move in search of a feeding site and do not move afterwards. They suck sap on all plant parts above the ground. Their feeding may cause yellowing of leaves followed by leaf drop, poor growth, dieback of branches, fruit drop, and blemishes on fruits.

Leaves may dry when heavily infested, and young trees may die.

Soft scales excrete honeydew, causing growth of sooty mould. In heavy infestations fruits and leaves are heavily coated with sooty mould turning black. Heavy coating with sooty mould reduces photosynthesis. Fruits contaminated with sooty mould loose market value. Ants are usually associated with soft scales. They feed on the honeydew excreted by soft scales, preventing a build-up in sooty moulds, but also protecting the scales from natural enemies.

Armoured scales do not excrete honeydew.

- Scales are attacked by a large range of parasitic wasps and predators. These natural enemies usually control scales. Outbreaks are generally related to the use of broad-spectrum pesticides that kill natural enemies, and or to the presence of large number of ants.

- Chemical control is possible with light mineral oils, at low concentrations (0.5-1%), mixed with other insecticides. At high concentrations, mineral oils may be harmful to the trees. Sprays should target young stages of the scales.

- Oil sprays should be carried out after picking and not during flowering or during periods of excessive heat or drought.

- To protect natural enemies alternate tree rows can be sprayed each season.

- At early stages of an outbreak cut and burn affected branches and leaves.

Larvae of ladybird beetles (Cheilocorus sp) feeding on red scales on an orange fruit

© A. M. Varela, icipe

Scales and…

Scale dama…

Armoured s…

The citrus rust mite (Phyllocoptruta oleivora)

The yellow tiny citrus rust mite attacks mainly the fruit. Its feeding causes the rind of the fruit to turn silvery, reddish brown, or blackish. One result of mite damage is small fruit, which deteriorates rapidly. This damage lowers the market value of the fruit. Heavy populations of the rust mite cause bronzing of leaves and green twigs, and general loss of vitality of the whole tree. Warm and humid conditions favour the development of rust mite.

- Some predatory mites feed on the rust mites, but they cannot control heavy infestations.

Damage by the citrus rust mite (Phyllocoptruta oleivora) on a "Washington Navel" orange fruit

© A. A. Seif, icipe

The citrus bud mite (Aceria sheldoni)

It is a tiny, worm-shaped, creamy white mite. It has only two pair of legs, and is hardly visibly without a magnifying glass. These mites occur in protected places such as under the bracts of buds. They attack the growing points of the twigs, causing malformation of the young leaves and flower buds. As a consequence, the growth of the trees is retarded.

The fruit set can be seriously reduced and infested fruit may be malformed. Bud mites are more abundant during the hot season. Commonly found in developing and leaf buds. Damage under the bracts causes the death of the buds. Flower bud development is reduced, growth is retarded, branches become stunted and deformed, and rosette-shaped leaves are formed. The fruits, particularly in lemons are deformed. Almost all deformed fruits fall off at an early stage of development. Even light infestations may cause damage and control measures should be applied on time and regularly. Spots decrease the market value of the fruit and provide entry for fungal infection.

Damage fruits loose moisture rapidly and do not keep well. Infestation on ripe fruits causes light yellow or silver discolouration. These mites attack all citrus species, but damage is usually worst in lemons. Damaged fruit could drop prematurely or assume abnormal shapes. The juice content of damaged fruit is significantly lower than that of normal fruit.

- The bud mites are not well controlled by natural enemies, and use of biopesticides is necessary for their management.

- Sulphur at a concentration of 2% controls both the rust and bud mites. However, sulphur kills also beneficial mites and may disrupt the natural control of other potential citrus pests. Sulphur must not be used at a temperature exceeding 30° C. A 4 week interval must be maintained between sulphur and oil sprays. No other pesticides or mixtures may be added to sulphur.

Citrus bud mite damage (Aceria sheldoni)

© A.A. Seif, icipe

Mealybugs

Several species of mealybugs attack citrus. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruit. Feeding on the fruit results in discoloured, bumpy, and scarred fruit, with low market value, or unacceptable for the fresh fruit market. Mealybugs excrete honeydew, which leads to the growth of sooty mould on fruit and leaves. Fruit cover with sooty mould at harvest must be washed. The most important is the citrus mealybug (Planoccous citri).

- Mealybugs frequently are under effective control by a wide range of natural enemies (parasitic wasps, lacewings, ladybird beetles etc.) and do not cause economic damage. However, if the natural balance is disturbed by application of pesticides or by presence of ants, mealybug populations may increase to damaging levels.

Mealybugs on citrus (Planoccous citri)

© A.M. Varela, icipe

Ants

Certain ants are major indirect pests in citrus orchards. Although they do not damage the trees, they are associated to honeydew-producing insects such as soft scales, aphids, whiteflies, blackflies and mealybugs.

Natural enemies often keep these insects under control; however, ants feeding on the honeydew give them indirect protection by disturbing natural enemies. As a result numbers of these honeydew producing insects, and indirectly other pests such as armoured scales, may rise to damaging levels.

Ant management does not imply eradication of all ants. There are many different types of ants in citrus orchards. Many of them are important predators of other insects, including pests of citrus. Some of the species that could be a problem due to their association with honeydew-producing insects (e.g. the big headed ant Pheidole megacephala and the pugnacious ant, Anoplolepis custodiens are also beneficial preying on a variety of insects, and are valuable predators on the ground. Therefore these ants should not be destroyed but kept off the trees.

- Undesirable ants can be kept out of the citrus trees by banding the stems with sticky stripes, or by spraying the tree trunks with insecticides.

- To keep these ants out of the trees low branches on the tree must be pruned and all weeds that touch the canopy must be removed, so that they do not provide access to the tree for the ants.

- When using sticky bands, they must circle completely around the stem. In addition, they should be checked regularly for efficiency. Sticky bands (strips) soon become non-adhesive in dusty and windy conditions. Moreover, over time insects get stuck to the bands clogging them and forming bridges, which the ants can cross. Therefore regular applications of the sticky substances are needed.

- Sticky substances (e.g. grease) may burn the bark, particularly, in young trees under direct sunlight. Therefore, it should not be applied directly to the trunks, but using polyurethane stripes as a base.

Brown house ants streaming up and down the white-washed trunk of an orange tree

© Bedford ECG, de Villiers EA. Courtesy of Ecoport www.ecoport.org.

Red fire ants or weaver ants (Oecophylla longinoda)

A particular case is that of the red fire ants or weaver ants which nest on citrus and other fruit trees (guava, soursop, cashewnuts, coconut palms among others). These ants are present in many countries in Africa. They are common in the coastal regions in East Africa.

They built nests on trees by joining leaves with silk produced by the larvae. These ants are very active moving on the trees and on the ground in search of food. They are highly voracious feeding on a large range of insects visiting the trees, and are important in controlling many insect pests in fruit trees and coconut palms. In spite of these benefits, weaver ants are considered by some as a pest due to their aggressiveness combined with painful bites, which makes fruit picking difficult, and to their association with honeydew-producing insects. They can foster the build-up of these insect pests, but it has been observed that they do kill some of them when the amount of honeydew produced by these insects is bigger than the amount required by the colony of weaver ants.

The benefits provided by predatory ants feeding or deterring insect pests must be outweighed against the damage they may cost indirectly. As a whole weaver ants are considered beneficial. They have been used actively in China for the control of citrus pests for centuries (Way and Khoo, 1992). Experienced farmers in Asia and Africa have developed their own methods to deal with the inconvenience of weaver ants during harvesting.

- A common practice among farmers is to throw wood ash on the branches of the tree they want to climb. The ants fall down of the branches and have difficulties to return giving time to the farmer to harvest.

- Other farmers rub their hands and arms with wood ashes, to prevent the ants from attacking them.

- Other rub their arms and feet with certain repellent products before climbing the tree, using protective clothing or harvest at times of the day when weaver ants are least active (Van Mele and Cuc, 2007)

Weaver ant nest on a citrus tree

© A.A. Seif, icipe

Nematodes

More than 40 nematode species have been associated with citrus worldwide. The economically important species are the citrus nematode (Tylenchulus semipenetrans) and the burrowing nematode (Radopholus similis).

1) The citrus nematode (T. semipenetrans)

It causes a slow decline of citrus trees. Affected trees show reduced vigour, small yellow leaves, defoliation, die-back of twigs, and small fruits. The citrus nematodes are ectoparasitic and sedentary. Only females are parasitic on roots. They are found on the surface of fibrous roots under debris-covered egg masses embedded in a gelatinous matrix. The life cycle, from egg to egg, is completed within 6-8 weeks at temperatures of 24-26° C. Optimal reproduction occurs at 28-31° C. Soil salinity increases the population density of citrus nematode. In affected orchards, populations of the nematode are concentrated in upper soil layers. Movement of plant material and soil is responsible for the spread of the nematode. Also agricultural implements and water (irrigation or rain) spread the nematode in a citrus orchard.

2) The "burrowing nematode" (Radopholus similis)

It is called "burrowing nematode" on account of the cavities and tunnels it produces in the root tissues. Symptoms are generally present on groups of trees that increase in number with time, hence, the name, spreading decline.

Symptoms are much more severe than in the case of T. semipenetrans and the spread is much quicker. Affected trees show fewer and smaller leaves and an abundance of dead twigs and branches. Trees wilt during periods of lack of moisture but generally the trees are not killed. It is an endoparasitic and migratory. Two distinct races of the nematode are known: the banana and citrus race. The former is known to attack banana roots but not citrus. The citrus race attacks bananas and citrus. The life cycle requires 18-21 days at 24-26° C, the optimum temperature being 24° C.

Burrowing nematodes migrate through roots and from root to root to feed. The nematodes are rarely found in the top 10 cm of the soil, highest populations being between 30 and 180 cm. Primary spread is thorough propagating infested seedlings.

- Use certified nematode-free planting stocks.

- Use tolerant / resistant rootstocks.

- Use cultural practices that enhance plant growth.

Lemon tree infested with citrus nematodes (Tylenchulus semipenetrans)

© Bedford ECG, de Villiers EA (EcoPort)

The citrus woolly whitefly (Aleurothrixus floccosus)

The citrus woolly whitefly was reported for the first time in East and Central Africa in the early to mid 90s. Serious attacks on citrus were observed in Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda. The adults of this whitefly resemble small white moths, covered with mealy white wax. Eggs are laid on the lower surface of young leaves. The young stages resemble soft scale insects and have a woolly appearance. They produce large quantity of honeydew that leads to the growth of sooty mould on the infested trees. This may cause defoliation, loss of fruits and dwarfing of trees. Small, mottled fruits are produced.

- The citrus woolly whitefly is kept under control by its natural enemies in its area of origin. In the mid to late 90s, one of the most efficient parasitic wasp (Cales noacki), which has controlled this pest in many countries, was introduced and released in Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda. Data collected in Kenya and Uganda showed that this parasitic wasp is effectively controlling the citrus woolly whitefly.

- Use of pesticides should be avoided since it may kill this parasitic wasp. Moreover, chemical control is not economically feasible. Pesticides are often inefficient since the immature stages are covered by wax. When effective, pest resurgence commonly occurs within a few weeks of application.

Immature stages of the citrus woolly whitefly (Aleurothrixus floccosus)

© B. Loehr, icipe

Citrus woo…

Citrus woo…

The citrus blackflies (Aleurocanthus woglumi and A. spiniferus)

Adults of the citrus blackflies resemble tiny (1.3 to1.7 mm in length) greyish moths. Eggs are usually laid in a spiral pattern on the lower surface of leaves. The immature stages are shiny black scale-like insects and are up to 1.2 mm in length. A white fringe of wax surrounds the body of older larvae and the pupae.

The insects are most noticeable as groups of very small, black spiny lumps on leaf undersides. They produce a large amount of honeydew, which accumulate on leaves and stems and usually develop black sooty mould fungus, which cover the leaves blackening the foliage and sometimes the whole plant. Ants may be attracted by the honeydew. Heavy infestation causes general weakening and eventual death of plants due to sap loss and the development of sooty mould on leaves. Infested leaves may be distorted.

- Citrus blackfly has been effectively controlled by natural enemies. This is the most cost-effective and sustainable method of control, and the parasitoids are capable of controlling it wherever it becomes established (e.g. Encarsia opulenta, Eretmocerus serius as natural enemies in Kenya).

- Spraying with neem seed extract (4%) at the emergence of new flush and repeated at 10 days intervals once or twice is recommended in India (Tandon, 1997).

- In case of localised infestations affected shoots should be removed and destroyed.

Immature stages of blackflies on a citrus leaf (Aleurocanthus woglumi) and (A. spiniferus). The whitish is parasitised by a fungus.

© A. A. Seif, icipe

Citrus bla…

Citrus bla…

Citrus aphids (Toxoptera citridus and T. aurantii)

They are small (1 to 3mm in length), brown to black in colour, and may be winged (having 2 pair of wings) or wingless. They feed by sucking on new growth and blossoms. High numbers are found on the leaf surfaces during the period of flushing (production of new shoots) and stems of attacked young shoots die back. Attacked leaves are curled and distorted. Flower buds are damaged or drop. Aphids excrete large amounts of honeydew. Leaves and fruits may turn black due to the growth of sooty mould. Symptoms can be severe on flush growth during dry periods following rainy spells.

Citrus aphids transmit tristeza and other virus diseases in citrus. The black citrus aphid T. citridus is the most efficient vector of the citrus tristeza virus.

- Citrus aphids are frequently kept in check by natural enemies, especially ladybird beetles, lacewings, hoverflies and parasitic wasps. Aphids are likely to become less of a problem if their natural enemies are not destroyed by pesticides.

- Management of ants may increase the efficiency of these natural enemies.

- Insecticides should be applied only when heavy aphid populations are developing on the new flush. Only infested shoots should be treated, especial attention should be given to the lower leafsurface.

- Neem products are reported to give good control of this aphid. Good control has been reported by the application of a 2% Neem Seed Kernel Extract (NSKE) at the beginning of the infestation on lime to kept this aphid below the economic threshold level in the field in India. For more information on neem click here (Jotti et al., 1990).

Heavy attack by the citrus aphid (Toxoptera citridus and T. aurantii)

© A.A. Seif, icipe

The citrus leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella)

The caterpillar of the citrus leafminer usually attacks young leaves and shoots. It mines the undersurface of young leaves, but it can attack both leaf surfaces, in heavy infestations, and occasionally the fruit. Its feeding causes serpentine mines that have a silvery appearance and reach a length of 5 to 10 cm. The middle of the mines is marked by a light or a dark coloured stripe, which consists of the excreta of the caterpillars. The caterpillars are greenish yellowish and are to 4 mm in length. Caterpillars pupate within the mine, near the leaf margin, under a slight curl of the leaf. The moths are tiny (2 to 3 mm long), greyish white in colour with fringed wings.

Eggs look like small dew drops and are usually laid on the underside of the leaves. Attacked young leaves are twisted, show brown patches of dead tissue and eventually fall off.

Heavy infestations can interfere with photosynthesis because of the reduction in leaf surface. This pest is especially troublesome in citrus nurseries. It can kill young nursery plants. This leafminer was a frequently observed pest during a survey of major citrus pests conducted in Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia in 1995 (B. Löhr, personal communication).

- In Asia, mineral oils and neem extracts (neem seed extract 2%) are recommended for control of the citrus leafminer (Tandon, 1997).

- Neem water extracts (1kg neem cake / 10l water) has given protection against this pest for up to 2 weeks (Zebitz, in Schmuttererr, 1995). In South China 1.4% emulsified neem oil gave protection against this pest in the nursery and also in young and old citrus trees (GTZ, 2001). For more information on neem click here.

Mining caterpillar of the citrus leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella) usually attacks young leaves and shoots.

© A.A. Seif, icipe

Citrus lea…

Citrus lea…

The African citrus psyllid (Trioza erytreae)

It prefers cool climates and it is found in Kenya only at elevations above 800 m. The adult is about 2 mm long, brownish yellow with long transparent wings with market veins. They resemble winged aphids. The adults jump and fly short distances when disturbed. When feeding, adults take up a distinctive position, with the abdomen raised. The orange-yellow eggs are laid on the edges of tender young leaves. They can be distinguished with the naked eye as a yellow fringe to the leaf. After hatching the nymph moves only a very short distance and settles down to feed on the underside of leaves. Once settled, it does not move again unless disturbed. They resemble small green or yellow scale insects, and are up about 1 mm long. Parasitised nymphs are dark brown to black in colour. Pit-like depressions are formed beneath the nymphs bodies. These depressions look like raised bumps on the upper side of the leaves, and remain even after the nymphs have become adults.

As result of these pock marks young leaves may be severely deformed, and flush growth depressed. They also cause damage by sucking sap from the leaves. However, in general, these types of damage do not seriously affect infested trees. The main damage caused by the citrus psyllid is as the vector of the greening disease, a major disease of citrus. A few psyllids in an orchard can spread the greening disease, but when high numbers are present, the spread is particularly rapid. It is therefore necessary to manage the citrus psyllids to retard the spread of the greening disease.

- Several natural enemies attack the citrus psyllid. Predators such as lacewings, spiders, predatory mites, ladybird beetles and hover flies feed on the citrus psyllid, but often they cannot control this pests effectively. Parasitic wasps play an important role in the control of citrus psyllids. Psyllaephagus pulvinatus attacks nymphs in Kenya and South Africa, and Tamarixia (Tetrastichus) dryi attacks nymphs in South Africa. In Reunion, the African psyllids has been successfully controlled by the introduction of T. dryi, from South Africa.

- Prevention of the spread of the citrus psyllids is crucial for managing greening disease. Drenching should be preferred method of pesticide application to avoid killing of the natural enemies. This should be done at onset of rains.

Adult of the African citrus psyllid (Trioza erytreaea)

© A. A. Seif, icipe

African ci…

African ci…

African ci…

The citrus thrips (Scirtothrips aurantii)

Citrus thrips are tiny insects (0.7 to 1 mm in length), and orange yellow in colour. Young stages are wingless, but adults have 2 pairs of narrow wings. Damage is caused by larvae and adults feeding on young twigs, leaves and fruits. Thrips feeding produces brown blemishes on the rind. Typical damage is the presence of rings of brown russet marks around the stem of the fruit. The damage is cosmetic and does not affect eating quality. However, external fruit blemishes can be so severe that the fruits are unmarketable. New shoots can be severely damaged. If thrips are abundant on young twigs, their feeding causes deformation of the twigs, which become thickened and distorted. In severe infestations, the leaves are deformed; young leaves are underdeveloped and drop when touched.

- Neem is effective against this thrips species.

This is a close-up of a related thrips species (Frankinella occidentalis). Immature thrips (left) and adults. Very much enlarged. Real size 0.9 to 1.1 mm.

© A.M. Varela, icipe

The false codling moth (Cryptophlebia leucotreta)

It is small (wingspan of 16-20 mm), dark brown to grey in colour. The moths are active at night. Female moths lay single eggs on ripening citrus fruits. The young caterpillar mines just beneath the surface, or bores into the pith causing premature ripening of the fruit and fruit drop.

The initial symptom on the fruit is a yellowish round spot with a tiny dark centre where the insect entered the fruit. In a later stage brown patches appear on the skin, usually with a hole in the centre. The young caterpillar is creamy-white with a dark brownish head. With age the body turn pinkish red. The fully-grown caterpillar is 15 to 20 mm in length. When mature the caterpillar leaves the fruit and pupates in the soil or beneath surface debris. Navel oranges seem to be the most heavily attacked. Grapefruit is less susceptible. In lemons and limes larval development is rarely, if ever, completed.

- Proper orchard sanitation in combination with egg and larval parasitoids normally keep this pest under control.

- Infested fruits (both on the tree and fallen fruits) should be removed regularly (twice a week), and buried at least 50 cm deep, or dump in a drum with water mixed with a little used oil. The fruits should be left in the drum for 1 week.

- This moth also attacks cotton, maize, castor, tea, avocado, guava and carambola fruits. Other host plants include wild guava plants, oak trees and wild castor among others. These other host plants should be included in the sanitation programme.

- If possible wild host plants should be removed from around the orchard. This pest is recorded in many African countries.

Caterpillar of the false codling moth (Cryptophlebia leucotreta)

© A. M. Varela, icipe

The false …

The false …

Fruit flies (Bactrocera invadens, Ceratitis capitata and C. rosa)

Several species of fruit flies are pests of citrus in Africa. In East Africa the most important are B. invadens, a new species of fruit fly recently introduced in the region, and C. capitata (Sunday Ekesi, personal communication). The female fly lays eggs within the skin of ripening fruits. Spots develop on the skin where eggs were laid and the hatching larva enters the fruit. The attacked area becomes soft, turns brown and decays as a result of secondary infection.

- These pests are controlled by orchard sanitation and application of baits.

- Monitoring fruit flies to determine when they arrive in the orchard is very important for the management of these pests.

Egg laying marks by fruit flies on an orange fruit

© A.A Seif, icipe

Fruit flie…

The swallowtail butterfly (Papilio demodocus)

The caterpillars of the swallowtail butterfly are also known as "orange dog". The butterfly is black with yellow markings on the wings, and has a wingspan of about 10 cm. They are common during the rainy season. Female butterflies lay whitish, grey eggs mainly on the tender terminal twigs and leaves. The caterpillars are white-brown, or green in colour. Most spines disappear as the caterpillar grows. Young caterpillars are brownish with white patches and are spiny. They resemble fresh bird droppings. Older caterpillars are green with some light markings and two eye-like spots at both sides of the front part of the body. When disturbed caterpillars shoot out a fleshy, forked retractable organ, through a slit behind the head, which gives off a repulsive smell.

Fully grown caterpillars are about 5 cm long. Caterpillars feed specially on the new growth of citrus trees. They can cause extensive damage to young trees, especially in citrus nurseries where their feeding can cause complete defoliation of the plant.

- Control is usually necessary on the nursery and on young trees (up to 2 years old). Several natural enemies such as parastitic wasps, and birds attack the caterpillars.

- Hand picking and destruction of caterpillars and eggs usually provides satisfactory control on small trees provided the plants are regularly checked.

- Neem products have been shown to provide satisfactory control of this pest (Schmutterer, 1995). In particular weekly applications of neem water extracts effectively controlled this pest on sweet orange seedlings in Gambia (Rednap, 1981). For more information on neem click here

The swallowtail butterfly (Papilio demodocus) also known as orange dog. Adult moth.

© A.M. Varela, icipe

Orange dog…

Orange dog…

Indirect Control Methods:

- Promotion of beneficial insects and plants by habitat management: organic orchard design, ecological compensation areas with hedges, nesting sites etc.

- Soil management: organic compost and plant slurry to improve soil structure and soil microbial activity

- Pruning: provides good aeration of the trees

Direct Control Methods:

- Biological control: release of antagonists, natural predators and entomophagous fungi.

- Mechanical control methods.

- Organic pest and disease control products.

- Use of disease-free planting material to avoid disease problems

- Choosing rootstocks and cultivars that are tolerant or resistant to prevalent diseases

- Application of fungicides such as copper, sulphur, clay powder and fennel oil. Copper can control several disease problems. However, it must not be forgotten that high Copper accumulations in the soil is toxic for soil microbial life and reduce the cation exchange capacity

Damping-off (Rhizoctoni solani) and Phytophthora spp.

Damping-off of citrus is most often caused by Rhizoctonia solanispp. Phytophthora spp. The typical symptom of damping-off is dying of seedlings just after emergence from the soil. However, damping-off fungi can also cause seed rot, resulting in sparse stands of seedlings in nursery beds.

- Damping-off diseases are favoured by abundant moisture in the soil. Adequate control of damping-off diseases can be achieved by avoiding infested soils and overwatering.

- In case of Phytophthora spp., seeds must be hot water treated. For more information on hot water treatment click here.

- Contaminated soil, tools or irrigation water should not be used in or near seedbeds.

Phytophtora on citrus tree

© A.A. Seif, icipe

Greening disease

It is caused by a bacterium (Candidatus Liberibacter africanus). The disease is transmitted by citrus psyllids (Trioza erytreae) and through use of budwood obtained from diseased trees. The disease is not soil-borne. It is not seed-borne and it is not mechanically transmitted.

Symptoms on the leaves show mottling, yellowing of veins or zinc defiency (i.e. small leaves, interveinal chlorosis and brush-like growth). Zinc deficiency induced by greening is confined to one or several branches within a tree (sectoral infection).

Trees infected by greening are distributed within the orchard randomly. Affected branches bear few fruits and in some cases do not fruit. The affected fruits are usually under-developed, reduced in size, lopsided, start to colour from the stem end instead of the stylar end as in the case with healthy fruits. Affected fruits drop prematurely. In seedy citrus varieties, seed abortion occurs. Severely diseased trees exhibit open growth, sparse chlorotic foliage, dieback of branches and severe fruit drop.

In Kenya, the disease is not found below 800 m above sea level because both the bacterium causing the disease and citrus psyllids are sensitive to high temperatures. Optimum temperature for symptom expression is 21 to 24°C; symptoms are masked above 26° C. The disease is especially destructive to sweet oranges and mandarins. It is less severe on lemon, grapefruit, citron and West Indian lime.

Rootstocks have no effect on greening disease.

- Use disease-free budwood

- Strict control of citrus psyllids.

- Very severely infected trees not producing economical yield should be up-rooted. If only a few branches are affected, they can be pruned out.

- Diseased young citrus trees should be replaced, as they will never bear fruit.

Greening disease

© A.A. Seif, icipe

Citrus gre…

Citrus gre…

Phaeoramularia fruit and leaf spot

The disease is caused by fungus Phaeoramularia angolensis. The disease is favoured by wet, cool conditions. On leaves, the fungus produces circular, mostly solitary (single) spots that are up to 10 mm in diameter with light brown or greyish centres. Each spot is usually surrounded by a yellow halo. Occasionally, the thin necrotic tissue in the centres of old spots falls out, creating a shot-hole effect. During rains, leaf spots on young leaves often join together ending in generalised chlorosis. Premature defoliation takes place when leaf petioles are infected. On fruit, the spots are circular to irregular in shape or joining together and surrounded by yellow halos. Most spots measure up to 8 mm in diameter. On young fruits, symptoms often start with nipple-like swellings without yellow halos.

Spots on mature fruits are normally flat, and often a dark brown to black sunken margin similar to anthracnose around the spots is observed. Fruits of more than 40 mm in diameter are somehow resistant to the disease. The disease has been observed on all citrus species including grapefruit, lemon, lime, mandarin, pummelo and orange. Grapefruit, mandarin, pummelo and orange are very susceptible. Lemon is less susceptible and lime is least susceptible. The disease can reduce yield by 50 to 100%.

- The disease can be effectively be controlled by a number of fungicides including copper based products.

- Successive use of coppers may cause stippling (dot-like marks) on the fruits.

Orange fruits infected by Phaeoramularia fruit spot (Phaeoramularia angolensis)

© A.A. Seif, icipe

Phaeoramul…

Phaeoramul…

Phaeoromul…

Citrus tristeza virus (CTV)

It has been found in all citrus growing areas of the world. It is spread by infected propagative material and several species of aphids (Toxoptera citricidus, T. aurantii, Aphis gossypii, A. craccivora, A. spiraecola and Myzus persicae).

T. citricidus is the most efficient vector of CTV. The virus has also been transmitted from plant to plant by the use of dodder (Cuscuta americana and C. subinclusa). CTV is not transmitted through citrus seeds. Most species of Citrus are hosts for CTV. The virus has naturally occurring field strains, which vary considerably in their ability to cause symptoms on different host plants and in the intensity of the symptoms expressed.

Symptoms caused by these strains include:

Seedling yellows (SY): This symptom consists of leaf yellowing and stunting in sour orange, grapefruit and lemon seedlings. This is a field problem when trees infected with SY strains of CTV are top-worked with grapefruit or lemon.

Decline on sour orange: Sweet orange, grapefruit or tangerine scions on sour orange rootstock become dwarfed, yellow (chlorotic), and often die. The decline may occur over a period of several years or very rapidly (quick decline). Trees that decline slowly generally have a bulge (swelling) above the bud union, and honeycombing (many fine holes or pitting) is present on the inner face of bark flaps removed from the sour orange rootstock. When trees decline rapidly, honeycombing does not occur, but a brown line may be observed at the bud union after the bark is removed. When budwood infected with decline-inducing strains is propagated on sour orange seedlings, the trees produced are stunted and unthrifty.

Stem-pitting on limes, grapefruit and sweet orange. Severely affected trees are stunted and may have bushy appearance. Leaves are yellow, and the twigs are brittle and break easily when bent. When the bark is removed from the affected twigs, elongated pits are seen in the wood. Trees affected by stem pitting have reduced yield and fruit quality is poor. Some strains cause longitudinal pits in the trunk, resulting in ropey appearance, and when bark is removed from the depressed parts deep pits can be seen in the wood.

- A practical safeguard against CTV is to use only disease-free budwood and to ensure that they budded onto tolerant rootstocks.

- In Brazil, where CTV has been the major problem of citrus, its control has been achieved by use of budlines pre-immunized with mild strains of the virus to protect against severe strains.

- It is, economically, impossible to prevent CTV spread by aphid control. However, selected control, at early stages of infection and during periods with high aphid populations, reduces the rate of spread.

- Remove infected trees.

- Rootstock varieties generally considered tolerant to CTV are Sweet orange, Cleopatra mandarin, Rough lemon, Rangpur lime and Trifoliate orange.

Citrus tristeza virus

© Richard Lee (Courtesy of EcoPort, www.ecoport.org)

Phytophthora-induced diseases (Phytophthora spp.)

They cause the most serious soil-borne diseases of citrus. These fungi are worldwide in distribution and cause citrus production losses in irrigated, arid areas as well as in areas with high rainfall. Diseases caused by Phytophthora spp. include damping-off in seedbeds, gummosis and brown rot of fruits. The most widespread and important Phytophthora spp. are P. nicotianae and P. citrophthora. Others of lesser importance in the tropics are P. citricola, P. hibernalisand P. palmivora. The most serious disease caused by Phytophthora spp. is gummosis (also known as foot rot).

Gummosis: An early symptom of gummosis is gum oozing from small cracks in the infected bark around the bud-union giving the affected trees a bleeding appearance. Citrus gum, which is water soluble, disappears after heavy rains. Severely affected tress have yellow foliage that eventually drops and twigs die-back often with a crop of small-sized fruits still hanging from bare branches. The feeder roots are destroyed when the root cortex is attacked; turn soft and easily separate giving the root system a stringy appearance. In an advanced stage, the trunk becomes girdled (encircled) and the affected trees decline and eventually die.

Gummosis is favoured by high moisture in the soil. Infection of fruit by Phytophthora spp. produces brown rot. The affected area is light brown, leathery and not sunken compared with the adjacent rind. Under humid conditions, white fungal growth (mycelium) forms on the rind surface. In the orchard, fruits on or near the ground become infected when they are splashed with water or come in contact with soil that is infested by Phytophthora spp.

Most of the infected fruits drop, but those that are harvested may not show symptoms until after they have been held in storage for a few days. Brown rot epidemics are usually restricted to areas where rainfall coincides with early stages of fruit maturity. It is important to note that most Phytophthora spp. are seed-borne.

- Treat citrus seeds with hot water at 50° C for 10 minutes (just too warm to keep a finger in for any amount of time)

- Soil drenches of copper based fungicide (allowed under organic farming in East Africa) are useful in preventing Phytophthora diseases in the nursery.

- Use tolerant or resistant rootstocks. Trifoliate orange is resistant. Swingle citrumelo, sour orange, rough lemon, and citranges (Carrizo and Troyer) are tolerant.

- Bud seedlings at a height of 25 cm and above, which will keep the bud union well above ground level.

- Avoid transplanting on heavy or poorly drained soils.

- Do not heap soil around the tree base.

- Avoid basin and flood irrigation. Do not over irrigate and ensure water does not contact the bud union.

- Avoid injuries to roots and trunks when cultivating.

- Gummosis can be halted by bark surgery before 50% of the trunk is affected. Scrape away dead bark tissue, remove about 10 mm margin of healthy tissue and paint the wound with a slurry of copper-based fungicide (allowed under organic production) or under non-organic production with metalaxyl or fosetyl-Al.

- Do not replant citrus into planting sites where other citrus has been grown and proven unhealthy.

Phytophthora-gummosis on grapefruit tree

© A.A. Seif, icipe

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum spp.)

There are 3 anthracnose diseases of citrus caused by Colletotrichum spp. Post-bloom fruit drop, which affects flowers of all citrus species and induces drop of fruitlets and is caused by C. acutatum. Lime anthracnose, which attacks all juvenile tissues of only Mexican lime, is also caused by this Colletotrichum species. C. gloeosporioides causes a rind blemish on fruit, especially grapefruit, in the field.

Post-bloom fruit drop

Description: C. acutatum infects petals and produces water-soaked lesions that eventually turn pink and then orange brown as the fungus sporulates. Infected fruitlets abscise at the base of the ovary, and the floral disk, calyx, and peduncle remain attached to the tree, forming structures commonly referred to as 'buttons'. Leaves surrounding an affected inflorescence are usually small, chlorotic, and twisted and have enlarged veins. Warm, wet weather favours disease development.

Lime anthracnose

Description: It affects only Mexican lime. It attacks flowers, young leaves, young shoots and fruits. Infected fruitlets abscise, and 'buttons' are produced as in postbloom fruit drop. In severe cases, young leaves become totally blighted and drop, and shoot tips die-back, producing wither tip symptoms. The fruit lesions are often large and deep, and cause fruit distortion. The disease is favoured by warm, wet weather.

Rind blemish on fruit

Description: The disease is caused by C. gloeosporioides. It is particularly severe on grapefruits. The blemish appears as a superficial, reddish brown discolouration, often in the form of tear stains, which usually appears following prolonged light rains in warm weather.

- Avoid overhead irrigation (opt for under-tree sprinklers where feasible)

- Wide tree spacing to reduce relative humidity within tree canopy

- Pruning of dead tree tissues

- Copper preventive sprays

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum spp.) on Key lime leaves

© Courtesy of www.aspnet.org

Anthracnos…

Anthracnos…

- AIC (2003). Fruits and vegetables technical handbook. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Bohlen, E. (1973). Crop pest in Tanzania and their control. Federal Agency for Economic Cooperation (BFE). Veralgh Paul Parey. ISBN 3-489-64826-9

- CAB International (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 Edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

- Citrus. Farming in South Africa. Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops. Published by the ARC.

- Foester, P., Varela, A., Roth, J. (2001). Best practices for the introduction of non-synthetic pesticides in selected cropping systems. Experiences gained form selected crops in developing countries. With contributions of C.V. Boguslawski, Mr Katua and G. Ratter. GTZ. Division 45 Rural Development.

- GTZ-Integration of Tree Crops into Farming Systems Project (2000). Tree Crop Propagation and Management - A Farmer Trainer Training Manual. BMZ/GTZ/ UNEP/ Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Kenya.

- Jurgen Griesback (1992). A Guide to Propagation and Cultivation of Fruit Trees in Kenya. Technical Cooperation - Federal Republic of Germany, Eschborn. ISBN: 3-88085-482-3

- KARI. Use green manure legumes to restore soil fertility: A guide for coastal farmers. Mtwapa, Kenya

- National Horticultural Research Station (1984). Horticultural Crops Protection Handbook. By Beije, C.M., Kanyagia , S.T., Muriuki, S.J.N., Otieno, E.A., Seif, A.A. and Whittle, A.M. KEN/75/028 and KEN/80/017. Thika. Kenya.

- Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

- Redknap, R. S. (1981). The use of crushed neem berries in the control of some insect pests in Gambia. IN Schmutterer et al. (Eds). Natural pesticides from the neem tree. Proc. 1st International Neem Conference, Germany 1980. pp 205-214.

- Schmutterer, H. (Ed) (1995). The neem tree Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and other meliaceous plants sources of unique natural products for integrated pest management, industry and other purposes. (1995). In collaboration with K. R. S. Ascher, M. B. Isman, M. Jacobson, C. M. Ketkar, W. Kraus, H. Rembolt, and R.C. Saxena. VCH. ISBN: 3-527-30054-6

- Seif, A.A. (1988). Comparison of green and yellow water traps for sampling citrus aphids at the Kenya Coast. East African Agricultural and Forestry Journal 53 (3): 159-161

- Seif, A.A. (2000). Phaeoramularia fruit and leaf spot of citrus. In: Compendium of Citrus Diseases, 2nd. Edition, APS Press, The American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA

- Seif, A.A., Hillocks, R.J. (1993). Phaeoramularia fruit and leaf spot of citrus with special reference to Kenya. International Journal of Pest Management 39 (1): 44-50

- Seif, A.A., Hillocks, R.J. (1997). Chemical control of Phaeoramularia fruit and leaf spot of citrus in Kenya. Crop Protection 16 (2): 141-145

- Seif, A.A., Hillocks, R.J. (1998). Some factors affecting infection of citrus by Phaeoramularia angolensis in Kenya. Journal of Phytopathology 146/8-9: 385-391

- Seif, A.A., Hillocks, R.J. (1999). Reaction of some citrus cultivars to Phaeoramularia fruit and leaf spot in Kenya. Fruits 54 (5): 323-329

- Seif, A.A., Islam, A.S. (1988). Population densities and spatial distribution patterns of Toxoptera citricida (KirK) (Aphididae) on citrus at the Kenya Coast. Insect Science Application 9 (4): 535-538

- Seif, A.A., Whittle, A.M. (1984). Diseases of citrus in Kenya. FAO Plant Protection Bulletin 32 (4): 122-127

- Seif, A.A., Whittle, A.M. (1984). Greening disease of citrus. National Horticultural research Station, Thika.TCP/KEN/2307. pp.32

- Tandon, P. L. (1997). Management of insect pests in tropical furit crops. In Tropical Fruit in Asia. Diversity, maintenace, conservation and use. Proceedings of the IPGRI-ICAR-UTFANET Regional training coiurse on the conservation and use of germplams of tropical fruits in Asia. May 1997. Bangalore , India, pp. 235-245.

- Timmer, L.W., S.M. Garnsey and J.H. Graham (Editors) (2000): Compendium of Citrus Diseases. 2nd. Edition. The American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA. ISBN: 0-89054-254-248-1

- Van Mele, P., Cuc, N. T.T. (2007). Ants as friends. Improving your tree crops with weaver ants. (2nd edition). Africa Rice Center (WARDA), Cotonou, Benin and CABI, Egham, U.K. 72 pp. ISBN: 92-913-3116.

- Way, M.J., Khoo, K. C. (1992). Role of ants in pest management. Annual Review of Entomology. 37:479-503.

- Corner Shop, Nairobi. cls@mitsuminet.com

- Food Network East Africa Ltd. info@organic.co.ke +2540721 100 001

- Green Dreams. admin@organic.co.ke +254721 100 001

- HCDA. md@hcda.or.ke www.hcda.or.ke +2542088469

- Kalimoni Greens. kalimonigreens@gmail,com +254722 509 829

- Karen Provision Stores, Nairobi. karenstoresltd@yahoo.com +25420885552

- Muthaiga Green Grocers, Nairobi

- Nakumatt Supermarket info@nakumatt.net 020551809

- National Horticultural Research Centre, KARI, Thika. karithika@gmail.com. +2546721281

- Uchumi Supermarket info@uchumi.com +25420550368

- Zuchinni Green Grocers, Nairobi +254204448240